Category Archives: books to read

Steve Jobs

Watched Steve Jobs (2015) Danny Boyle | Written by Aaron Sorkin

To read Walter Isaacson‘s Steve Jobs.

Thoreau

Podcast Thoreau and the American Idyll

In Our Time Podcast BBC

Melvyn Bragg; Kathleen Burk, Professor of American History at University College London; Tim Morris, Lecturer in American Literature at the University of Dundee; Stephen Fender, Honorary Professor in English Literature at University College London.

Unitarianism

Jesus inspired by God but not divine.

Transcendentalism

-Ralph Waldo Emerson

Emerson-intuitive nature of the divine.

Romanticism:

-Walt Whitman

-Emily Dickinson

Dark Romanticism:

–Herman Melville

–Nathaniel Hawthorne

–Edgar Allan Poe

“The Dark romantic authors represented a response to the optimism of the ideology of Transcendentalism.” from “Dark Romanticism.” Dark Romanticism – New World Encyclopedia. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Feb. 2017.

Quaker’s Inward light, follow your own conscience.

Mexican-American War (1846-1848)

Socrates: The examined life is not worth living.

William Paley‘s Of the Duty of Civil Obedience

Roger Williams founder of Rhode Island and advocate of religious freedom (separation of church and state).

The End of the Affair

Greene, Graham. The End of the Affair. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1962. Print. First edition 1951.

…

Machiavelli’s The Prince

Podcast: Machiavelli: Nigel Warburton and Prof. Quentin Skinner

Machiavelli’s The Prince

The Prince as a centaur:

“He says that the ancients understood state craft better, when they figured The Prince as a centaur. The centaur is half man and half beast, and that’s what it is to understand state craft. Manly virtue will never be enough, you’ve got to be ready for beastliness, and the centaur is half beast. Now, that is presented directly as a satire of Cicero.”- Prof. Skinner

Cicero: the fox and the lion

“Cicero had said, ‘Force is beastly and is to be avoided, that is simply the lion. Fraud is beastly and that is to be avoided, that is simply the fox’. And Machiavelli says, ‘Since you need to know how to be beastly, you had better know which particular beasts to imitate, and then in the most famous phrase in the book he says, ‘Those who have done best as princes in our time have known how to imitate the lion and the fox’.” – Prof. Skinner

‘You’re going to have to cheat, you must do your best to appear not to be cheating’, and that again is satirical in respect of Cicero’s De Officiis, because one of the things which Cicero keeps telling us is, ‘Fraud will always be found out. So you cannot gain true glory by pretence’, I’m now quoting Cicero, ‘because your pretences will always find you out’ And that becomes a biblical thought too. ‘Be sure your sins will find you out’. Now, one of the most important things that Machiavelli wants to tell The Prince is not to worry about that, because it’s not true. And he’s very keen on the fact that The Prince is not performing his politics in republican conditions. In republican conditions, you’re out in the piazza, everyone has a vote, it’s all public. People are watching you. You’ve only been elected, their turn will come, it’s a communal activity, everything is in the bright light of day. It’s not so for The Prince.” – Prof. Skinner

From Chapters 15-24 “‘Be courageously evil where it’s necessary to be evil, but otherwise follow what people regard as the virtues as much as possible. Because if you don’t, they’ll hate you, and if they hate you, you’re in trouble’. -Prof. Skinner

See Shakespeare’s Iago

The Prince as a critique of Seneca‘s ‘De Clementia’, ‘De Beneficiis’ ‘concerning benefits’, and Cicero’s De Officiis, Concerning One’s Offices.

La muerte de Séneca. 1871. Manuel Domínguez Sánchez. Museo de Prado, Madrid. El título completo dado por el pintor fue: Séneca, después de abrirse las venas, se mete en un baño y sus amigos, poseídos de dolor, juran odio a Nerón que decretó la muerte de su maestro. Via Wikimedia.

La fortuna

Essarai non buono

“Machiavelli does himself say at one point in Chapter 15 – this pivotal and notorious chapter where he introduces the virtuoso prince who is not always virtuous. He says ‘I’m teaching you that sometimes you must learn, how not to be good’, and it’s interesting he doesn’t say there, virtuoso, he says buono, a good person. ‘Essarai non buono’ – how not to be a good person.”” – Prof. Skinner

Salus populi suprema lex esto (The health of the people should be the supreme law) from Cicero’s De Legibus.

Machiavellian morality vs. Christian morality and classical morality.

“If you’re a prince, you need to go against conventional Christian or classical morality, if you’re an ordinary person, perhaps, you may want to carry on according to Christian or classical morality.” -Prof. Skinner

Read:

Isaiah Berlin’s essay The Originality of Machiavelli

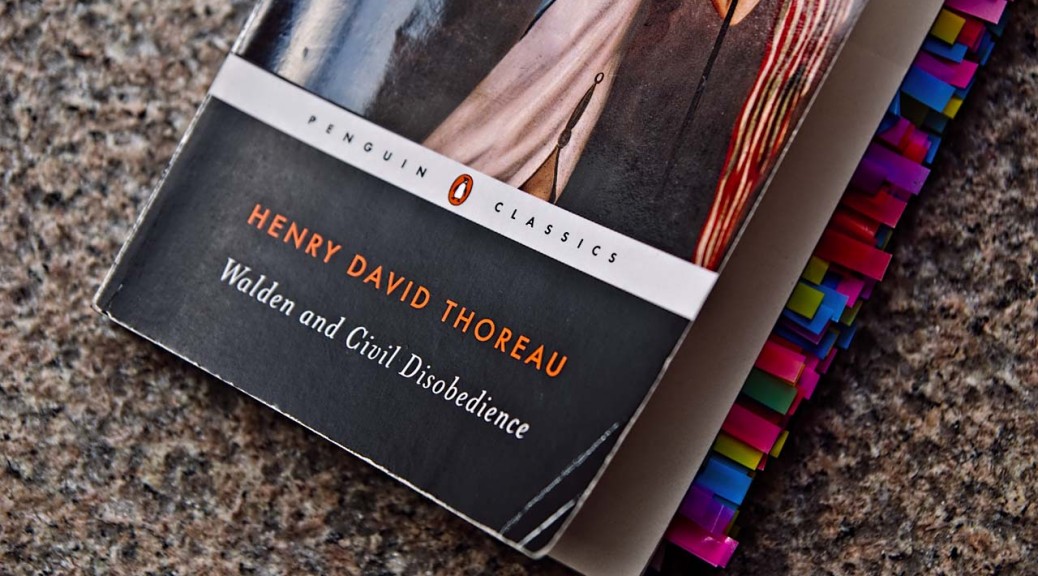

Walden and Civil Disobedience

Read:

Thoreau, Henry David., and Michael Meyer. Walden and Civil Disobedience. NY: Penguin, 1983. Print.

Walden first published 1854.

Civil Disobedience first published 1849.

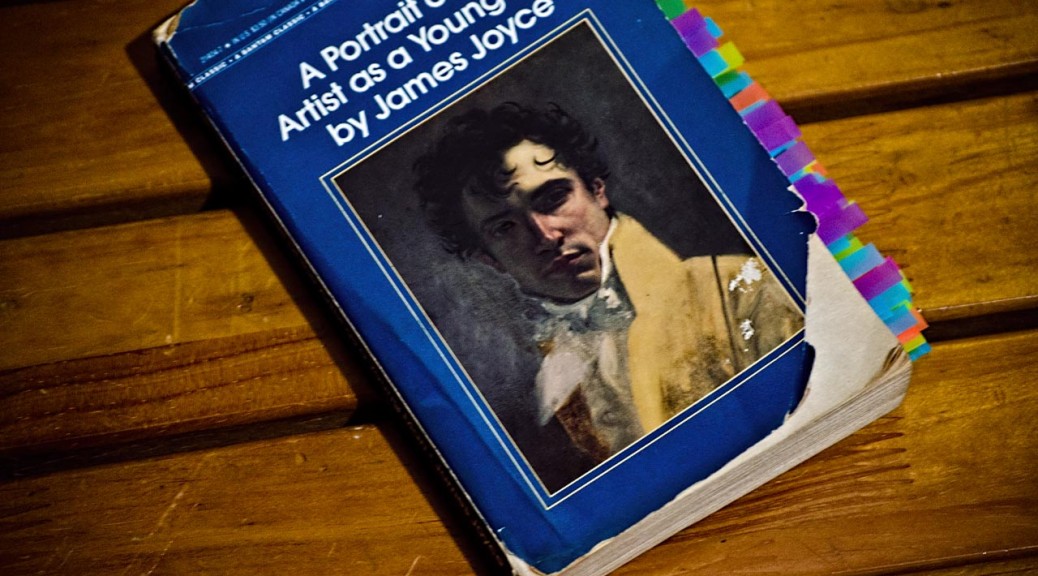

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (III)

Joyce, James. A Portrait of The Artist as a Young Man. New York: Bantam Books, 1992. Print. (First Edition 1916).

—

“sighting in the ascent, through a region of viscid gloom.

“He halted on the landing before the door and then, grasping the porcelain knob, opened the door quickly. He waited in fear, his soul pining within him, praying silently that death might not touch his brow as he passed over the threshold, that the fiends that inhabit darkness might not be given power over him. He waited still at the threshold as the entrance to some dark cave. Faces were there; eyes: they waited and watched.” p. 130

“He had sinned. He had sinned so deeply against heaven and before God that he was not worthy to be called God’s child.” p. 131

“His eyes were dimmed with tears and, looking humbly up to heaven, he wept for the innocence he had lost.” p. 133

“Once soul was lost; a tiny soul: his. It flickered once and went out, forgotten, lost. The end: black cold void waste.” p. 134

“and had first spoked of the kingdom of God to poor fishermen, teaching all men to be meek and humble of heart.” p. 135

“he called first to His side, the carpenters, the fishermen, poor and simple people following a lowly trade, handling and shaping the wood of trees, mending their nets with patience.” p. 135

“His blood began to murmur in his veins, murmuring like a sinful city summoned from its sleep to bear its doom. Little flakes of fire fell and powdery ashes fell softly, alighting on the houses of men. They stirred, waking from sleep, troubled by the heated air.” p. 136

“SUNDAY was dedicated to the mystery of the Holy Trinity, Monday to the Holy Ghost, Tuesday to the Guardian Angels, Wednesday to Saint Joseph, Thursday to the Most Blessed Sacrament of the Altar, Friday to the Suffering Jesus, Saturday to the Blessed Virgin Mary.” p. 141

“the three theological virtues, in faith in the Father Who had created him, in hope in the Son Who had redeemed him, and in love of the Holy Ghost Who had sanctified him;” p. 142

“Frequent and violent temptations were a proof that the citadel of the soul; had not fallen and that the devil raged to make it fall.” p. 147

“Some of the boys had then asked the priest if Victor Hugo were not the greatest French writer. The priest had answered that Victor Hugo had never written half so well when he had turned against the church as he had written when he was a catholic.” p. 150

“He had seen himself, a young and silentmannered priest, entering a confessional swiftly, ascending the altarsteps, incensing, genuflecting, accomplishing the vague acts of the priesthood which pleased him by reason of their semblance of reality and of their distance from it.” p. 152

Dieric Bouts,the older. At The Church of Saint Peter, Leuven, Belgium. Created: 1464 – 1467. Via Wikimedia.

“the order of Melchisedec.” p. 153

*****”He drew forth a phrase from his treasure and spoke it softly to himself:

-A day of dapled seaborne clouds.-

The phrase and the day and the scene harmonised in a chord. Words. Was it their colours? He allowed them to glow and fade, hue after hue: sunrise gold, the russet and green of apple orchards, azure of waves, the grey-fringed fleece of clouds. No, it was not their colours: it was the pose and balance of the period.” p. 160

askance

***”They were voyaging across the deserts of the sky, a host of nomads on the march, voyaging high over Ireland, westward bound. The Europe they had come from lay out there beyond the Irish Sea, Europe of strange tongues and valleyed and woodbegirt and citadelled and of entrenched and marshalled races.” p. 161

John Everett Millais – National Portrait Gallery. Via Wikimedia.

“His morning walk across the city had begun; and he foreknew that as he passed the sloblands of Fairview he would think of the cloistral silverveined prose of Newman; that as he walked along the North Strand Road, glancing idly at the windows of the provision ships, he would recall the dark humour of Guido Cavalcanti and smile; that as he went by Baird’s stone cutting works in Talbot Place the spirit of Ibsen would blow though him like a keen wind, a spirit of wayward boyish beauty;”p. 170

“His mind when wearied of its search for the essence of beauty amid the spectral words of Aristotle or Aquinas turned often for its pleasure to the dainty songs of the Elizabethans.” p. 170

“His thinking was a dusk of doubt and selfmistrust, lit up at moments by the lightnings of so clear a splendour that in those moments the world perished about his feet as if it had been fire consumed: and thereafter his tongue grew heavy and he met the eyes of others with unanswering eyes for he felt that the spirit of beauty had folded him round like a mantle and that in reveie at least he had been acquainted with nobility.” p. 171

“he had tried to peer into the social life of the city of cities through the words implere ollam denariorum which the rector had rendered sonorously as the filling of a pot with denaries.” p. 174

“but yet it wounded him to think that he would never be but a shy guest at the feast of the world’s culture and that the monkish learning, in terms of which he was striving to forge out an esthetic philosophy, was held no higher by the age he lived in than the subtle and curious jargons of heraldry and falconry.” p. 174

“the droll statue of the national poet of Ireland.” p. 174

“-Aquinas-answered Stephen-says pulcra sunt quæ visa placent.-” p. 180

“-In so far as it is apprehended by the sight, which I suppose means here esthetic intellection, it will be beautiful. But Aquinas also says Bonum est in quod tendit appetitus. In so far as it satisfies the animal craving for warmth fire is a good. In hell, however, it is an evil.-” p. 180

Nineteenth century Photochrom postcard of the Cliffs of Moher in County Clare in Ireland showing cliffside table and refreshments. Via Wikimedia.

“-These questions are very profound, Mr Dedalus-said the dean.-It is like looking down from the cliffs of Moher into the depth. Many go down into the depths and never come up. Only the trained diver can go down into those depths and explore them and come to the surface again.-” p. 181

“You know Epictetus?-

-An old gentleman-said Stephen coarsely-who said that the soul is very like a bucketful of water.-

-He tells us in his homely way-the dean went on-that he put an iron lamp before a statue of one of the gods and that a thief stole the lamp. What did the philosopher do? He reflected that it was in the character of a thief to steal and determined to buy and earthen lamp next day instead of the iron lamp.-” p. 181

“whether words are being used according to the literary tradition or according to the tradition of the marketplace. I remember a sentence of Newman’s, in which he says of the Blessed Virgin that she was detained in the full company of the saints. The use of the word in the marketplace is quite different. I hope I am not detaining you.-” p. 182

“That?-said Stephen.-Is that called a funnel? Is it not a tundish?-” p. 182

“-And to distinguish between the beautiful and the sublime-the dean added-to distinguish between moral beauty and material beauty. And to inquire what kind of beauty is proper to each of the various arts.” p. 184

“-In pursuing these speculations-said the dean conclusively-there is, however, the danger of perishing of inanition.” p. 184

The British Library – Image taken from page 274 of ‘Finland in the Nineteenth Century: by Finnish authors. Illustrated by Finnish artists. Via Wikimedia.

“-I may not have his talent-said Stephen quietly.

-You never know-said the dean brightly.-We never can say what is in us. I most certainly should not be despondent. Per aspera ad astra.-“

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (II)

Joyce, James. A Portrait of The Artist as a Young Man. New York: Bantam Books, 1992. Print. (First Edition 1916).

—

“The sentence of Saint James which says that he who offends against one commandment becomes guilty of all had seemed to him first a swollen phrase until he had began to grope in the darkness of his own state. From the evil seed of lust all other deadly sins had spring forth: pride in himself and contempt of others, covetousness in using money for the purchase of unlawful pleasures, envy of those whose vices he could not reach to and calumnious murmuring against the pious, gluttonous enjoyment of food, the dull glowering anger amid which he brooded upon his longing, the swamp of spiritual and bodily sloth in which his whole being had sunk.” p. 100

Francis Xavier

“the apostle of the Indies.” p. 102

Ignatius of Loyola

“A retreat, my dear boys, signifies a withdrawal for a while form the cares of our life, the cares of this workaday world, in order to examine the state of our conscience, to reflect on the mysteries of holy religion and to understand better why we are here in this world.” p. 104

“What doth it profit a man to gain the whole world if he suffer the loss of his immortal soul? Ah, my dead boys, believe me there is nothing in this wretched world that can make up for such a loss.” p. 104

“Banish from your minds all worldly thoughts, and think only of the last things, death, judgment, hell and heaven. He who remembers these things, says, Ecclesiastes, shall not sin for ever. He who remembers the last things will act and think with them always before his eyes.” p. 105

“What did it avail then to have been a great emperor, a great general, a marvellous inventor, the most learned of the learned? All were as on before the judgment seat of God.” p. 107

“The stars of heaven were falling upon the earth like the figs cast by the figtree which the wind has shaken. The sun, the great luminary of the universe, had become as sackcloth of hair. The moon was blood red. The firmament was a scroll rolled away. The archangel Michael, the prince of the heavenly host, appeared glorious and terrible against the sky. With one foot on the sea and one foot on the land he blew from the archangelical trumpet the brazen death of time. The three blasts of the angel filled all the universe. Time is, time was, but time shall be no more. At the last blast the souls of universal humanity throng towards the valley of Jehosaphat, rich and poor, gentle and simple, wise and foolish, good and wicked.” p. 107

Valley of Josaphat

Absalom

“O you who present a smooth smiling face to the world while your soul within is a foul swamp of sin, how will it fare with you in that terrible day?” p. 108

“Death is the end of us all. Death and judgement, brought into the world by the sin of our first parents, are the dark portals that close our earthly existence, the portals that open into the unknown and the unseen, portals through which every soul must pass, alone, unaided save by its good works, without friend or brother or parent or master to help it, alone and trembling.” p. 108

“Theologians consider that it was the sin of pride, the sinful thought conceived in an instant: non serviam: I will not serve. That instant was his ruin. He offended the majesty of God by the sinful thought of one instant and God cast him out of heaven into hell for ever.” p. 111

“Adam and Eve were then created by God and placed in Eden, in the plain of Damascus, that lovely garden resplendent with sunlight and colour, teeming with luxuriant vegetation. The fruitful earth gave them her bounty: beasts and birds were their willing servants: they knew not the ills our flesh is heir to, disease and poverty and death: all that a great and generous God could do for them was done.” p. 112

“-Alas, my dear little boys, they too fell. The devil, once a shining angel, a son of the morning, now a foul fiend came n the shape of a serpent, the subtlest of all the beasts of the field. He envied them. He, the fallen great one, could not bear to think that man, a being of clay, should possess the inheritance which he by his sin had forfeited for ever.” p. 112

“the damned are so utterly bound and helpless that, as a blessed saint, Saint Anselm, writes in his book on Similitudes, they are not even able to remove from the eye a worm that gnaws it.” p. 114

“-They lie in exterior darkness. For, remember, the fire of hell gives forth no light. As, as the command of God, the fire of the Babylonian furnance lost its heat by not its light so, at the command of God, the fire of hell, while retaining the intensity of its heat, burns eternally in darkness. It is a neverending storm of darkness, dark flames and dark smoke of burning brimstone, amid which the bodies are heaped one upon another without even a glimpse of air. Of all the plagues with which the land of the Pharaohs was smitten one plague alone, that of darkness, was called horrible.” p. 114

” And then imagine this sickening stench, multiplied a millionfold and a millionfold again from the millions upon millions of fetid carcasses massed together in the reeking darkness, a huge and rotting human fungus. Imagine all this and you will have some idea of the horror of the stench of hell.” p. 115

“Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire which was prepared for the devil and his angels!-” p. 118

“He passed up the staircase and into the corridor along the walls of which the overcoats and waterproofs hung like gibbeted malefactors, headless and dripping and shapeless. And at every step he feared that he had already died, that his soul had been wrenched forth of the sheath of his body, that he was plunging headlong though space.” p. 118

“The English lesson began with the hearing of the history. Royal persons, favourites, intriguers, bishops, passed like mute phantoms behind their veil of names. All had died: all had been judged. What did it profit a man to gain the whole world if he lost his soul? At last he had understood: and human life lay around him, a plain of peace whereon antilike men laboured in brotherhood, their dead sleeping under quiet mounds.” p. 119-120

“-Sin, remember, is a twofold enormity. It is a base conssent to the promptings of our corrupt nature to the lower instincts, to that which is gross and beastlike; and it is also a turning awat from the counsel of our higher nature, from all that is pure and holy, from the Holy God Himself. For this reason mortal sin is punished in hell by two different forms of punishment, physical and spiritual.” p. 121

***”Now imagine a mountain of sand, a million miles high, reaching from the earth to the farthest heavens, and a million miles broad, extending to remotest space, and a million miles in thickness: and imagine such an enormous mass of countless particles of sand multiplied as often as there are leaves in the forest, drops of water in the mighty ocean, feathers on birds, scales on fish, hairs on animals, atoms in the vast expanse of the air: and imagine that as the end of every million years a little bird came to that mountain and carried away in its beak a tiny grain of that sand. How many millions upon millions of centuries would pass before that bird had carried away even a square foot of that mountain, how many eons upon eons of ages before it had carried away all. Yet at the end of that immense stretch of time not even one instant of eternity could be said to have ended; even then, at the end of such a period, after that eon of time the mere thought of which makes our very brain reel dizzily, eternity would have scarcely begun.” p. 125-126

“The ticking went on unceasingly; and it seemed to this saint that the sound of the ticking was the ceaseless repetition of the words; ever, never. Ever to be in hell, never to be in heaven; ever to be shut off from the presence of God, never to be shut off from the presence of God, never to enjoy the beatific vision; ever to be eaten with flames, gnawed by vermin, goaded with burning spikes,” p. 126

“-As sin, an instant of rebellious pride of the intellect, made Lucifer and a third part of the cohorts of angels fall from their glory.” p. 127-128.

Books January 2017

Giuttari, Michele, and Howard Curtis. A Death in Tuscany. London: Abacus, 2009. Print.

Giuttari, Michele, and Howard Curtis. A Death in Tuscany. London: Abacus, 2009. Print.

(I) Joyce, James. A Portrait of The Artist as a Young Man. New York: Bantam Books, 1992. Print. (First Edition 1916).

(I) Joyce, James. A Portrait of The Artist as a Young Man. New York: Bantam Books, 1992. Print. (First Edition 1916).

(V) Joyce, James. A Portrait of The Artist as a Young Man. New York: Bantam Books, 1992. Print. (First Edition 1916).

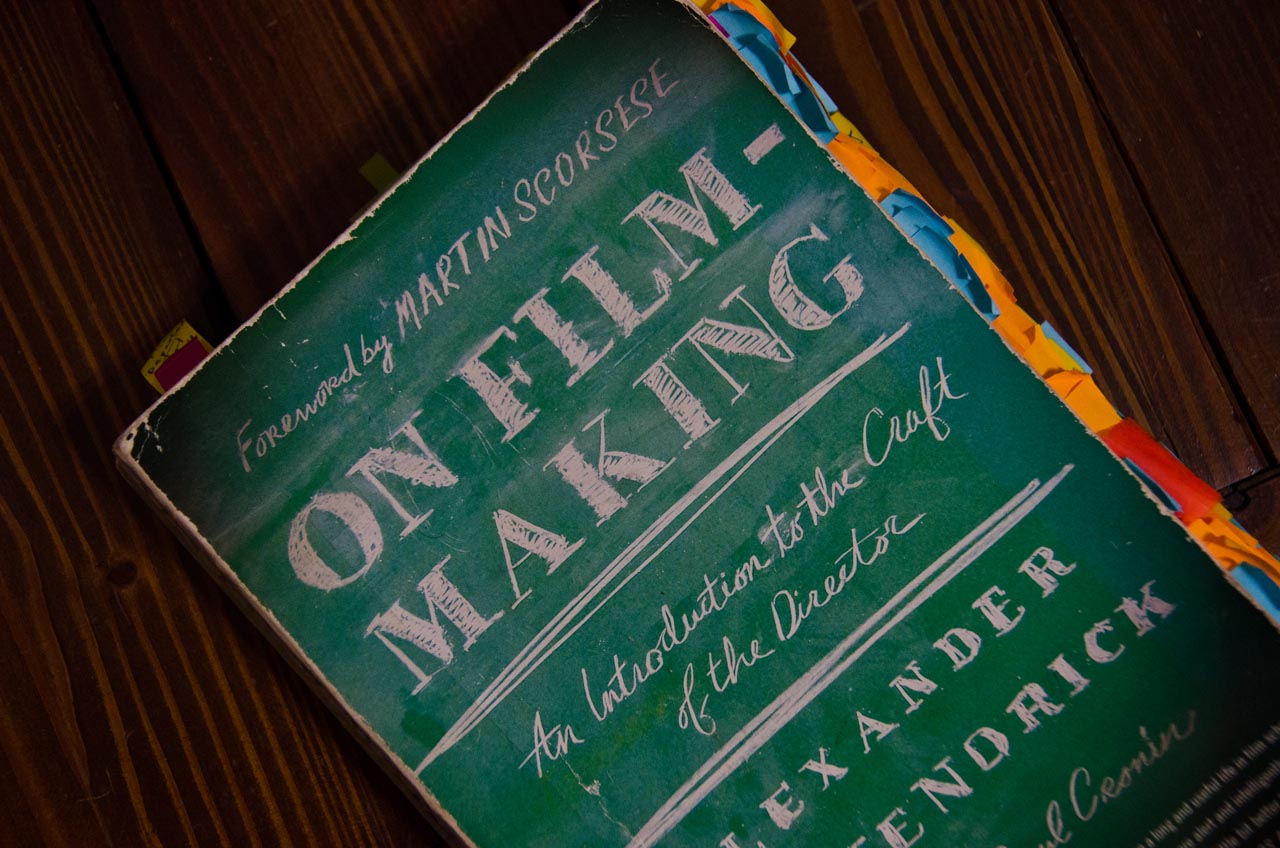

(I) Mackendrick, Alexander. On film-making: an introduction to the craft of the director. New York: Faber and faber, 2005. Print.

(I) Mackendrick, Alexander. On film-making: an introduction to the craft of the director. New York: Faber and faber, 2005. Print.

(II)

(III)

(IV)

(V)

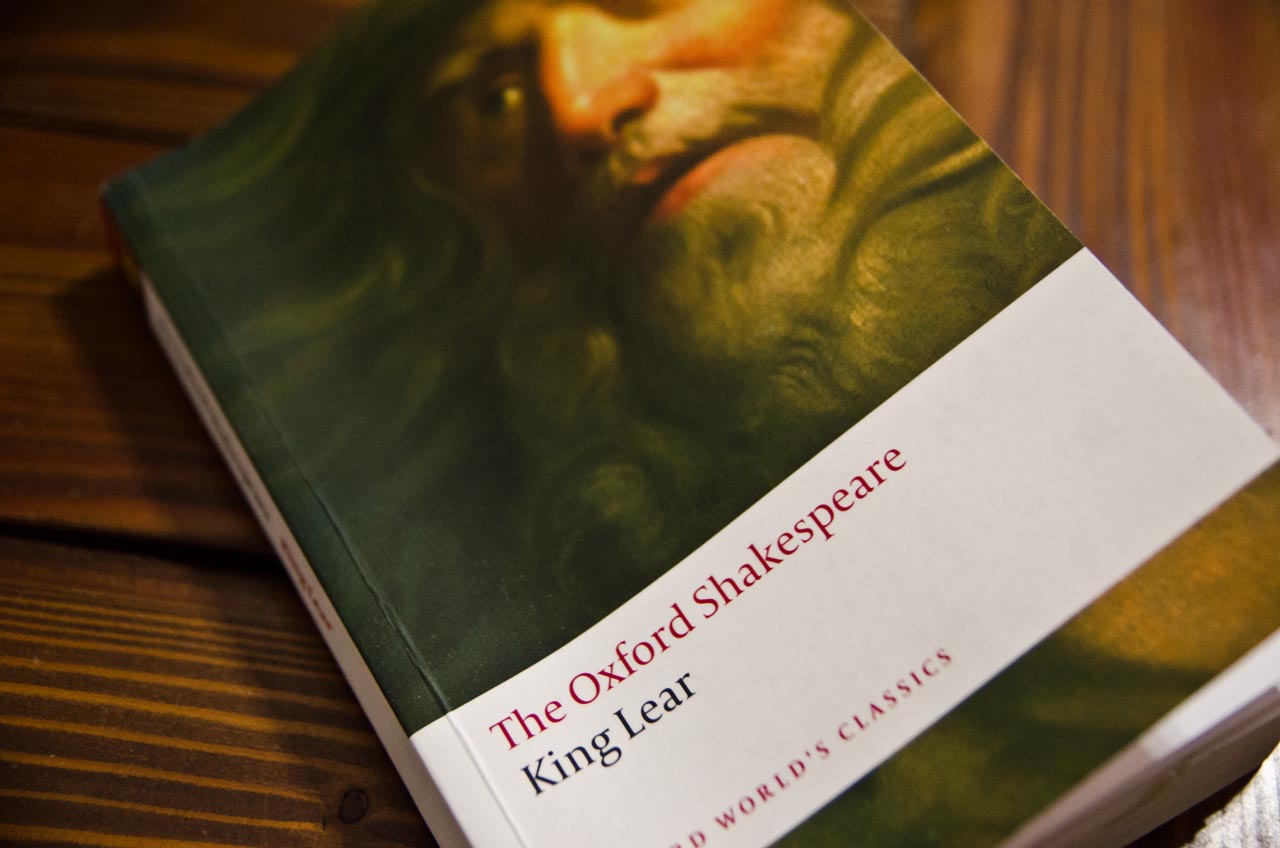

(I) Shakespeare, William, and Stanley Wells. The History of King Lear. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

(I) Shakespeare, William, and Stanley Wells. The History of King Lear. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

(II) Shakespeare, William, and Stanley Wells. The History of King Lear. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Wiesel, Elie, and Marion Wiesel. Night. New York, NY: Hill and Wang, a Division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006. Print. (First Ed. 1958).

Wiesel, Elie, and Marion Wiesel. Night. New York, NY: Hill and Wang, a Division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006. Print. (First Ed. 1958).

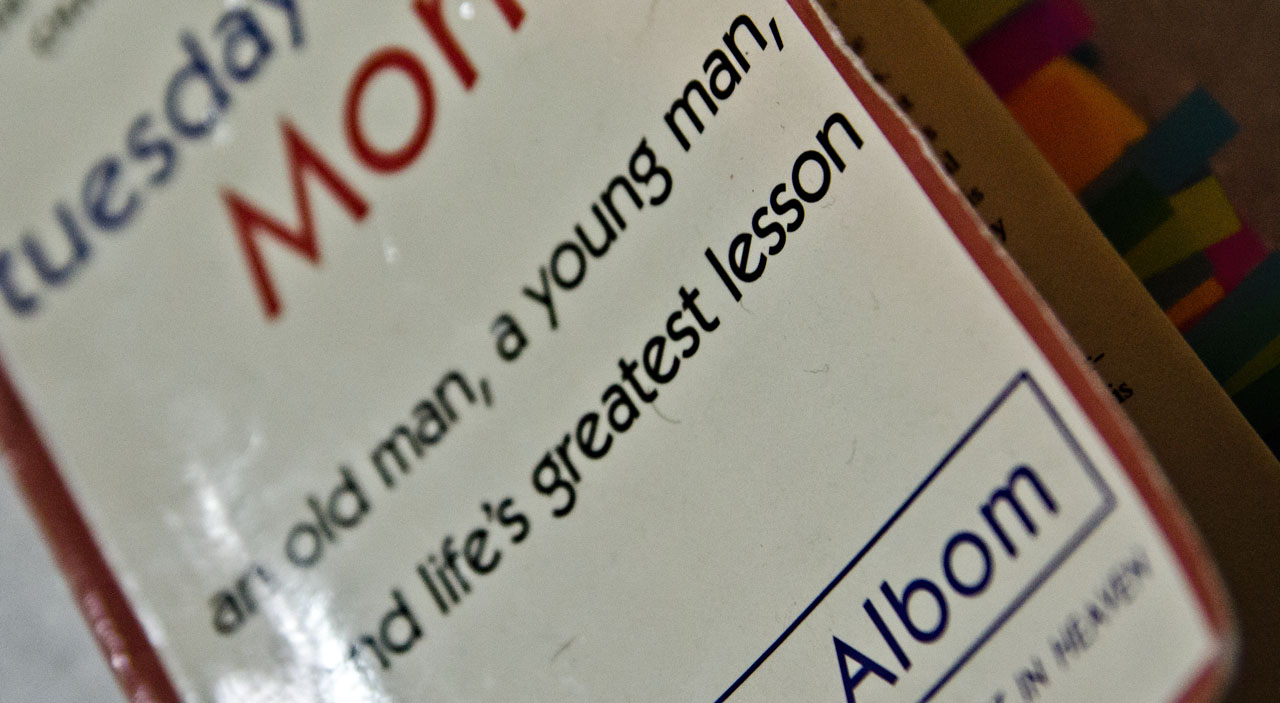

Albom, Mitch. Tuesdays With Morrie: an Old Man, a Young Man, and Life’s Greatest Lesson. New York: Anchor Books, 1997. Print.

Albom, Mitch. Tuesdays With Morrie: an Old Man, a Young Man, and Life’s Greatest Lesson. New York: Anchor Books, 1997. Print.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (I)

Joyce, James. A Portrait of The Artist as a Young Man. New York: Bantam Books, 1992. Print. (First Edition 1916).

—

To Read:

Finnegans Wake. 1939 (took Joyce seventeen years to write).

“Et ignotas animum dimittit in artes.” OVID, Metamorphoses, VIII., 18. (And he sets his mind to unknown arts) p. 1

“Then he heard the noise of the refectory every time he opened the flaps of his ears. It made a roar like a train at night. And when he closed the flaps the roar was shut off like a train going into a tunnel.” p. 7

“-Tell us, Dedalus, do you kiss your mother before you go to bed? Stephen answered:

-I do.

Wells turned to the other fellows and said:

-O, I say, here’s a fellow says he kisses his mother every night before he goes to bed.

The other fellows stopped their game and turned round, laughing. Stephen blushed under their eyes and said:

-I do not.

Wells said:

-O, I say, here’s a fellow says he doesn’t kiss his mother before he goes to bed.

They all laughed again. Stephen tried to laugh with them. He felt his whole body hot and confused in a moment. What was the right answer to the question?” p. 8

“But the Christmas vacation was very far away: but one time it would come because the earth moved round always.” p. 9

“There was a picture of the earth on the first page of his geography: a big ball in the middle of clouds. Fleming had a box of crayons and one night during free study he had coloured the earth green and the clouds maroon.” p. 9

“He turned to the flyleaf of the geography and read what he had written there: himself, his name and where he was.

Stephen Dedalus

Class of Elements

Clongowes Wood College

Sallins

County Kildare

Ireland

Europe

The World

The Universe” p. 10

County Kildare, Ireland

“What was after the universe? Nothing. But was there anything round the universe? Nothing. But was there anything round the universe to show where it stopped before the nothing place began? It could not be a wall but there could be a thin thin line there all round everything. It was very big to think about everything and everywhere. Only God could do that.” p. 10

Cork, Ireland.

“The corridors were darkly lit and the chapel was darkly lit. Soon all would be dark and sleeping. There was cold night air in the chapel and the marbles were the colour the sea was at night. The sea was cold day and night: but it was colder at night.” p. 12

“It would be lovely to sleep for one night in that cottage before the fire of smoking turf, in the dark lit by there fire, in the warm dark, breathing the smell of the peasants, air and rain and turf and corduroy. But, O, the road there between the trees was dark! You would be lost in the dark. It made him afraid to think of how it was.” p. 12

“The prefect’s shoes went away. Where? Down the staircase and along the corridors or to his room at the end? He saw the dark. Was it true about the black dog that walked there at night with eyes as big as carriagelamps? They said it was the ghost of a murderer. A long shiver of fear flowed over his body. He saw the dark entrance hall of the castle.” p. 13

“And the train raced on over the flat lands and past the Hill of Allen. The telegraph poles were passing, passing. The train went on and on. It knew. There were lanterns in the hall of his father’s house and ropes of green branches.” p. 14-15

See Fionn mac Cumhaill and the Fianna

Hill of Allen

***”Every rat had two eyes to look out of. Sleek slimy coats, little little feet tucked up to jump, black slimy eyes to look out of. They could understand how to jump. But the minds of rats could not understand trigonometry. When they were dead they lay on their sides. Their coats dried then. They were only dead things.” p. 16

“How pale the light was at the window! But that was nice. There fire rose and fell on the wall. It was like waves. Someone had put coal on and he heard voices. They were talking. It was the noise of waves. Or the waves were talking among themselves as they rose and fell.

He saw the sea of waves, long dark waves rising and falling, dark under the moonless night. A tiny light twinkled at the pierhead where the ship was entering: and he saw a multitude of people fathered by the water’s edge to see the ship that was entering their harbour.” p. 21

“Perhaps they had stolen a monstrance to run away with it and sell it somewhere. That must have been a terrible sin, to go in there quietly at night, to open the dark press and steal the flashing gold thing into which God was put on the altar in the middle of flowers and candles at benediction while the incense went up in clouds at both sides as the fellow swung the censer and Dominic Kelly sang the first part by himself in the choir. But God was not in it of course when they stole it. But still it was a strange and a great sin even to touch it.” . 40

Monstrance

“The word was beautiful: wine. It made you think of dark purple because the grapes were dark purple that grew in Greece outside houses like white temples. But the faint smell off the rector’s breath had made him feel a sick feeling on the morning of his first communion.” p. 41

“-Where did you break your glasses? repeated the prefect of studies.

-The cinderpath, sir.

-Hoho! The cinderpath! cried the prefect of studies. I know that trick.

Stephen lifted his eyes in wonder and saw for a moment Father Dolan’s whitegrey not young face, his baldy whitegray head with fluff at the sides of it, the steel rims of his spectacles and his no-coloured eyes looking through the glasses. Why did he say he knew that trick?

-Lazy idle little loafer! cried the prefect of studies. Broke my glasses! An old schoolboy trick! Out with your hand this moment!” p. 44

“A hot burning stinging tingling blow like the loud crack of a broken stick made his trembling hand crumple together like a leaf in the fire” p. 44

“Stephen knelt down quickly pressing his beaten hands to his sides. To think of them beaten and swollen with pain all in a moment made him feel so sorry for them as if they were not his own but someone else’s that he felt sorry for.” p. 45

“He saw the rector sitting at a desk writing. There was a skull on the desk and a strange solemn smell in the room like the old leather of chairs.

His heart was beating fast on account of the solemn place he was in and the silence of the room: and he looked at the skull and at the rector’s kind-looking face.” p. 50

“He would be very quiet and obedient: and he wished that he could do something kind for him to show him that he was not proud.” p. 53

“Stephen knelt at his side respecting, though he did not share, his piety. He often wondered what his granduncle prayed for so seriously. Perhaps he prayed for the souls in purgatory or for the grace of a happy death or perhaps he prayed that God might send him back a part of the big fortune he had squandered in Cork.” p. 56

“Trudging along the road or standing in some grimy wayside public house his elders spoke constantly of the subjects nearer their hearts, of Irish politics, of Munster and of the legends of their own family, to all of which Stephen lent an avid ear.” p. 56

“The hour when he too would take part in the life of that world seemed drawing near and in secret he began to make ready for the great part which he felt awaited him there nature of which he only dimly apprehended.

His evenings were his own; and he pored over a ragged translation of The Count of Monte Cristo. The figure of that dark avenger stood forth in his mind for whatever he had heard or divined in childhood of the strange and terrible.” p. 56

“Outside Blackrock, on the road that led to the mountains, stood a small whitewashed house in the garden of which grew many rosebushes: and in this house, he told himself, another Mercedes lived. Both on the outward and on the homeward journey he measured distance by this landmark: and in his imagination he lived through a long train of adventures, marvellous as those in the book itself, towards the close of which there appeared an image of himself, grown older and sadder, standing in a moonlit garden with Mercedes who had so many years before slighted his love, and with a sadly proud gesture of refusal, saying:

-Madam, I never eat muscatel grapes.” p. 57

To read:

Dantès sur son rocher, affiche de Paul Gavarni pour Monte Cristo d’Alexandre Dumas. 1846.

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

“He passed unchallenged among the docks and along the quays wondering at the multitude of corks that lay bobbing on the surface of the water in a thick yellow scum, at the crowds of quay porters and the rumbling carts and the ill dressed bearded policemen. The vastness and strangeness of the life suggested to him by the bales of merchandise stocked along the walls or swung aloft out of the holds of streamers wakened again in him the unrest which had sent him wandering in the evening from garden to garden in search of Mercedes.” p. 60-61

“He sat listening to the words and following the ways of adventure that lay open in the coals, arches and vaults and winding galleries and jagged caverns.

Suddenly he became aware of something in the doorway. A skull appeared suspended in the gloom of the doorway. A feeble creature like a monkey was there, drawn there by the sound of voices at the fire. A whining voice came from the door asking:

-Is that Josephine?” p. 62

To read:

Lord Byron:

Don Juan, Manfred, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Mazeppa, Hebrew Melodies.

The Bride of Abydos or Selim and Zuleika. Painting, 1857, by Eugène Delacroix depicting Lord Byron’s work.

“The light spread upwards from the glass roof making the theatre seem a festive ark, anchored among the hulks of houses, her frail cables of lanterns looping her to her moorings.” p. 69

“Then a noise like dwarf artillery broke the movement. It was the clapping that greeted the entry of the dumb bell team on the stage.” p. 69

“Stephen shook his head and smiled in his rival’s flushed and mobile face, beaked like a bird’s. He had often thought it strange that Vincent Heron had a bird’s face as well as a bird’s name.” p. 70

“-Here. It’s about the Creator and the soul. Rrm… rrm…rrm…Ah! without a possibility of ever approaching nearer. That’s heresy.

Stephen murmured:

-I mean without a possibility of ever reaching.

It was a submission and Mr Tate, appeased, folded up the essay and passed it across to him, saying:

-O…Ah! ever reaching. That’s another story.

But the class was not so soon appeased. Though nobody spoke to him of the affair after class he could feel about him a vague general malignant joy.” p. 73

“As soon as the boys had turned into Clonliffe Road together they began to speak about books and writers, saying what books they were reading and how many books there were in their father’s bookcases at home. Stephen listened to them in some wonderment for Boland was the dunce and Nash the idler of the class. In fact after some talk about their favourite writers Nash declared for Captain Marryat who, he said, was the greatest writer.

-Fudge! said Heron. Ask Dedalus. Who is the greatest writer, Dedalus?

Stephen noted the mockery in the question and said:

-Of prose do you mean?

-Yes.

-Newman, I think.

-Is it Cardinal Newman? asked Boland.

-Yes, answered Stephen.” p. 74

To read:

John Henry Newman

The Dream of Gerontius, Apologia Pro Vita Sua.

Naval officer and writer Frederick Marryat

See: Confiteor

“-Admit that Byron was no good.

-No.

-Admit.

-No.

-Admit.

-No. No.

At lasty after a fury of plunges he wrenched himself free. His tormentors set off towards Jone’s Road, laughing and jeering at him, while he, half blinded with tears, stumbled on, clenching his fists madly and sobbing.” p. 76

“While his mind had been pursuing its intangible phantoms and turning in irresolution from such pursuit he had heard about him the constant voices of his father and of his masters, urging him to be a gentleman above all things and urging him to be a good catholic above all things. These voices had now come to be hollow sounding in his ears.” p. 77

“He gave them ear only for a time but he was happy only when he was far from them, beyond their call, alone or in the company of phantasmal comrades.” p. 78

“He stood still and gazed up at the sombre porch of the morgue and from that to the dark cobbled laneway at its side.” p. 80

“-That is hose piss and rotted straw, he thought. It is a good odour to breathe. It will calm my heart. My heart is quite calm now. I will go back.” p. 80

****”As the train steamed out of the station he recalled his childish wonder of years before and every event of his first day at Clongowes. But he felt no wonder now. He saw the darkening lands slipping away past him, the silent telegraphpoles passing his window swiftly every four seconds, the little glimmering stations, manned by a few silent sentries, flung by the mail behind her and twinkling for a moment in the darkness like fiery grains flung backwards by a runner.” p. 81

“He listened without sumpathy to his father;s evocation of Cork and of scenes of his youth-a tale broken by sighs or draughts from his pocket flask whenever the image of some dead friend appeared in it, or whenever the evoker remembered suddenly the purpose of his actual visit.” p. 81

“They drove in a jingle across Cork while it was still early morning and Stephen finished his sleep in a bedroom of the Victorian Hotel.” p. 81

“His father was standing before the dressingtable, examining his hair and face and moustache with great care, craning his neck across the water jug and drawing it back sideways to see the better. While he did so he sang softly to himself with quaint accent and phrasing:

“‘Tis youth and folly

Makes young men marry,”” p. 82

“The consciousness of the warm sunny city outside his window and the tender tremors with which his father’s voice festooned the strange sad happy air, drove off all the mists of the night’s ill humour from Stephen’s brain.” p. 82

“Then he had been sent away from home to a college, he had made his first communion and eaten slim jim out of his cricket cap and watched the firelight leaping and dancing on the wall of a little bedroom in the infirmary and dreamed of being dead, of mass being said for him by the rector in a black and gold cope, of being buried then in the little graveyard of the community off the main avenue of lines. But he had not died then. Parnell had died.” p. 86-87

River Lee (Cork)

River Liffey (Dublin)

“His mind seemed older than theirs: it shone coldly on their strifes and happiness and regrets like a moon upon a younger earth. No life or youth stirred in him as it had stirred in them.” p. 89

“His childhood was dead or lost and with it his soul capable of simple joys and he was drifting amid life like the barren shell of the moon.

“Art thou pale for weariness

Of climbing heaven and gazing on the earth,

Wandering companionless?…” p. 89

To read:

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Prometheus Unbound, Ozymandias, Ode to the West Wind, To a Skylark, Music, When Soft Voices Die, The Cloud, The Masque of Anarchy.

Louis Édouard Fournier, The Cremation of Percy Bysshe Shelley, oil on canvas, Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery. Louis Édouard Fournier (1857-1917). Via Wikimedia.