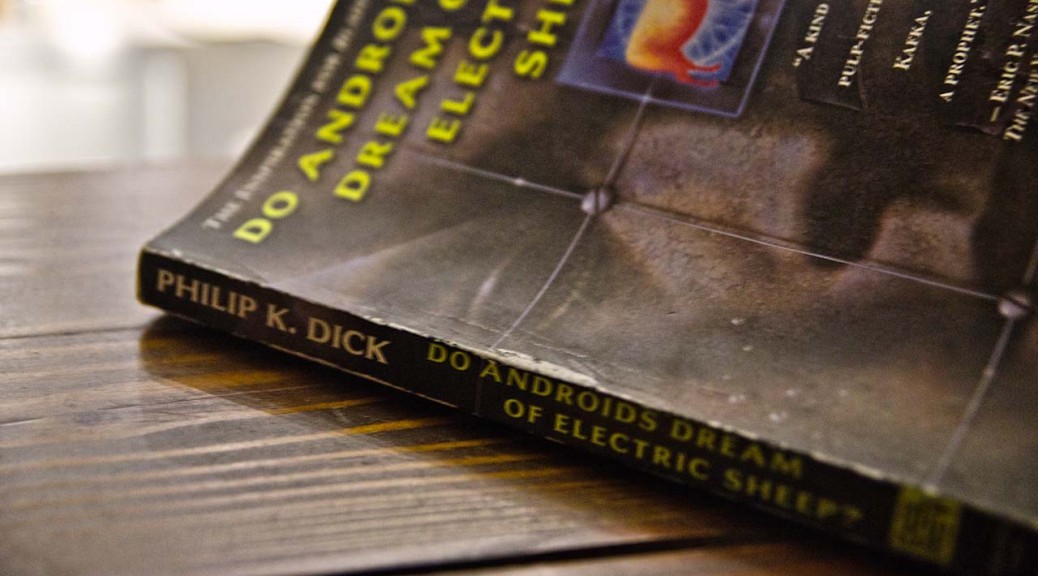

Dick, Philip K. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? New York: Del Rey, 1996. (First. ed 1968)

“But a mood like that,” Rick said, “you’re apt to stay in it, not dial your way out. Despair like that, about total reality, is self-perpetuating.” p. 6

“First, strangely, the owls had died. At the time it had seemed almost funny, the fat, fluffy white birds lying here and there, in yards and on streets; coming out no earlier than twilight, as they had while alive, the owls escaped notice. Medieval plagues had manifested themselves in similar way, in the form of many dead rats. This plague, however, had descended from above.” p. 15-16

“An android, no matter how gifted as to pure intellect capacity, could make no sense out of the fusion which took place routinely among the followers of Mercerism–an experience which he, and virtually everyone else, including subnormal chickenheads, managed with no difficulty.” p. 30

“Empathy, evidently, existed only within the human community, whereas intelligence to some degree could be found throughout every phylum and order including the arachnida. For one thing, the empathic faculty probably required an unimpaired group instinct; a solitary organism, such as a spider, would have no use for it; in fact it would tend to abort a spider’s ability to survive.” p. 30-31.

“Because, ultimately, the empathic gift blurred the boundaries between hunter and victim, between the successful and the defeated.” p. 31

“It retiring–i.e., killing–and andy, he did not violate the rule of life laid down by Mercer. You shall kill only the killers, Mercer had told them the year empathy boxes first appeared on Earth.” p. 31

“For Rick Deckard an escaped humanoid robot, which had killed its master, which had been equipped with an intelligence greater than that of many human beings, which had no regard for animals, which possessed no ability to feel empathic joy for another life form’s success or grief at its defeat–that, for him, epitomized The Killers. p. 32

“She indicated the owl dozing on its perch; it had briefly opened both eyes, yellow slits which healed over as the owl settled back down to resume its slumber.” p. 43

“Kipple is useless objects, like junk mail or match folders after you use the last match or gum wrappers or yesterday’s homeopage. When nobody’s around, kipple reproduces itself. For instance, if you go to bed leaving any kipple around your apartment, when you wake up the next morning there’s twice as much of it. It always gets more and more.” p. 65

***””No one can win against kipple,” he said, “except temporarily and maybe in one spot, like in my apartment I’ve sort of created stasis between the pressure of kipple and nonkipple, for the time being. But eventually I’ll die or go away, and then the kipple will again take over. It’s a universal principle operating throughout the universe; the entire universe is moving toward a final state of total, absolute kippleization.” He added, “Except of course for the upward climb of Wilbur Mercer.”” p. 65-66

“Every day he declined in sagacity and vigor. He and the thousands of other specials throughout Terra, all of them moving toward the ash heap. Turning into living kipple.” p. 73

“This rehearsal will end, the performance will end, the singers will die, eventually the last score of the music will be destroyed in one way or another; finally the name “Mozart” will vanish, the dust will have won.” p. 98

“An android,” he said, “doesn’t care what happens to another android. That’s one of the indications we look for.” p. 101

quondam

“disemelevatored” p. 126

Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch | The Scream (1893)

“The creature stood on a bridge and no one else was present; the creature screamed in isolation. Cut off by–or despite–its outcry.” p. 130

Edvard Munch | Puberty (1894-95)

Puberty. 1894-95 p. 131, 133

“She was really a superb singer, he said to himself as he hung the receiver, his call completed. It don’t get it; how can a talent like that be a liability to our society? But it wasn’t the talent, he told himself; it was she herself.” p. 137

“”You realize,” Phil Resch said quietly, “what this would do. If we include androids in our range of empathic identification, as we do animals.”

“We couldn’t protect ourselves.”” p. 141

“He had an indistinct, glimpsed darkly impression: of something merciless that carried a printed list and a gun, that moved machine-like through the flat, bureaucratic job of killing. A thing without emotions, or even a face; a thing that if killed got replaced immediately by another resembling it. And so on, until everyone real and alive had been shot.” p. 158

“But what does it matter to me? I mean, I’m a special; they don’t treat me very well either,” p. 163 (Isidore to Roy Baty)

“Rick said, “I took a test, one question, and verified it; I’ve begun to emphathize with androids,” p. 174

“The old man said, “You will be required to do wrong no matter where you go. It is the basic condition of life, to be required to violate your own identity. At some time, every creature which lives must do so. It is the ultimate shadow, the defeat of creation” p. 179

“Mercer talked to me but it didn’t help. He doesn’t know any more than I do. He’s just an old man climbing a hill to his death.” p. 179

“Do androids dream? Rick asked himself. Evidently: that’s why they occasionally kill their employers and flee here. A better life, without servitude.” p. 184

“this android stole, and experimented with, various mind-fusing drugs, claiming when caught that it hoped to promote in an androids a group experience similar to that of Mercerism,” p. 185

“Because without the Mercer experience we just have your word that you feel this empathy business” p. 209

“”The legs of toads are weak,” Rick said. “That’s the main difference between a toad and a frog, that an water. A frog remains near water but a toad can live in the desert” p. 240

“”The killers that found Mercer in his sixteenth year, when they told him he couldn’t reverse time and bring things back to life again. So now all he can do is move along with life, going where it goes, to death.” p. 242