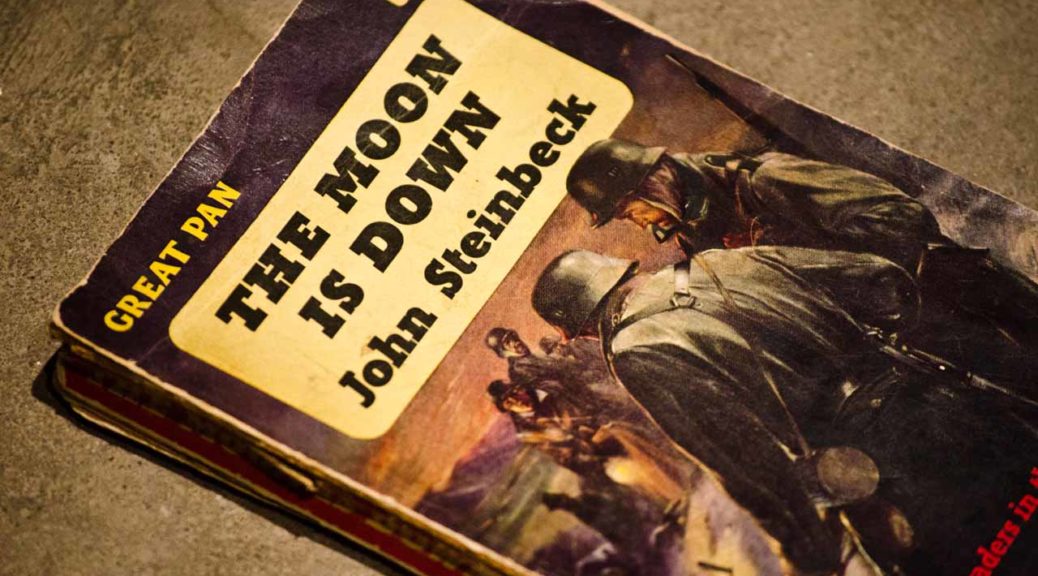

Steinbeck, John. The Moon Is Down. Pan Books LTD, 1961. First published 1942.

BANQUO How goes the night, boy?

FLEANCE The moon is down; I have not heard the clock.

Macbeth Act II, Scene i.

to watch: The Moon Is Down (1943) Irving Pichel.

BANQUO How goes the night, boy?

FLEANCE The moon is down; I have not heard the clock.

Macbeth Act II, Scene i.

to watch: The Moon Is Down (1943) Irving Pichel.

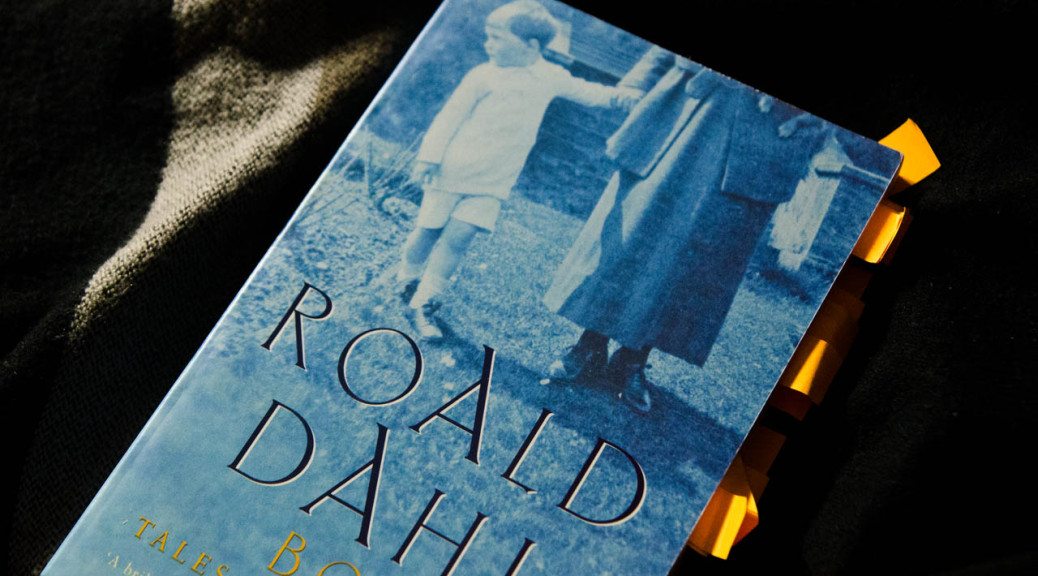

On his dad “He was a tremendous diary-writer. I still have one of his many notebooks from the Great War of 1914-18. Every single day during those five war years he would write several pages of comment and observation about the events of the time.” p. 18

“His theory was that if the eye of a pregnant woman was constantly observing the beauty of nature, this beauty would somehow become transmitted to the mind of the unborn bay within her womb and that baby would grow up to be a lover of beautiful things.” p. 19

“I can remember very clearly the journeys I made to and from the school because they were so tremendously exciting.” p. 23

“‘But how do they turn the rats into liquorice?’ the young Thwaites had asked his father.

‘They wait until they’ve got ten thousand rats,’ the father had answered, ‘then they dump them all into a hude shiny steel cauldron and boil them up for several hours.'” p. 30

“‘There is no cure for ratitis. I ought to know. I’m a doctor.'” p. 31

“Whether or not the wily Mr Coombes had chalked the cane beforehand and had thus made an aiming mark on my grey flannel shorts after the first stroke, I do not know. I am inclined to doubt it because he must have known that this was a practice much frowned upon by Headmasters in general in those days. It was not only regarded as unsporting, it was also an admission that you were not an expert at the job.” p. 50

“‘Skaal, Bestemama!’ She will then lift her own glass and hold it up high. At the same time your own eyes meet hers, and you must keep looking deep into her eyes as you sip your drink. After you have both done this, you raise your glasses high up again in a sort of silent final salute, and only then does each person look away and set down his glass.” p. 58

“There were the wooden skeletons of shipwrecked boats on those islands, and big white bones” p. 65

“In which direction from where I was lying was Llandaff?… Therefore, if I turned towards the window I would be facing home. I wriggled round in my bed and faced my home and my family.” p. 89-90

“‘Life is tough, and the sooner you learn how to cope with it the better for you.'” p. 98

Captain Hardcastle’s mustache “The only other way he could have achieved this curling effect, we boys decided, was by prolonged upward brushing with a hard toothbrush in front of the looking-glass every morning.” p. 109

“His eyes rover the Hall endlessly, searching for mischief. The only noises to be heard were Captain Hardcastle’s little snorting grunts and the soft sound of pen-nibs moving over paper.” p. 113

“‘I have learnt one thing about England,’ my mother went on. ‘It is a country where men love to wear uniforms and eccentric clothes.'” p. 139

“But Corkers, an eccentric old bachelor, was neither dull nor colourless. Corkers was a charmer, a vast ungainly man with drooping bloodhound cheeks and filthy clothes… He would come lumbering into the classroom and sit down at his desk and glare at the class. We would wait expectantly, wondering what was coming next.” p.150

“Another time, he brought a two-foot-long grass-snake into class and insisted that every boy should handle it in order to cure us for ever, as he said, of a fear of snakes.” p. 151-152

“The life of a writer is absolute hell compared with the life of a businessman. The writer has to force himself to work. He has to make his own hours and if he doesn’t go to his desk at all there is nobody to scold him.” p. 171

“A person is a fool to become a writer. His only compensation is absolute freedom. He has no master except his own soul, and that, I am sure, is why he does it.” p. 172