Wat Chaiwatthanaram, Ayutthaya, Thailand. August, 2016.

Wat Chaiwatthanaram, Ayutthaya, Thailand. August, 2016.

Wat Chaiwatthanaram, Ayutthaya, Thailand. August, 2016.

Wat Chaiwatthanaram, Ayutthaya, Thailand. August, 2016.

—

“sighting in the ascent, through a region of viscid gloom.

“He halted on the landing before the door and then, grasping the porcelain knob, opened the door quickly. He waited in fear, his soul pining within him, praying silently that death might not touch his brow as he passed over the threshold, that the fiends that inhabit darkness might not be given power over him. He waited still at the threshold as the entrance to some dark cave. Faces were there; eyes: they waited and watched.” p. 130

“He had sinned. He had sinned so deeply against heaven and before God that he was not worthy to be called God’s child.” p. 131

“His eyes were dimmed with tears and, looking humbly up to heaven, he wept for the innocence he had lost.” p. 133

“Once soul was lost; a tiny soul: his. It flickered once and went out, forgotten, lost. The end: black cold void waste.” p. 134

“and had first spoked of the kingdom of God to poor fishermen, teaching all men to be meek and humble of heart.” p. 135

“he called first to His side, the carpenters, the fishermen, poor and simple people following a lowly trade, handling and shaping the wood of trees, mending their nets with patience.” p. 135

“His blood began to murmur in his veins, murmuring like a sinful city summoned from its sleep to bear its doom. Little flakes of fire fell and powdery ashes fell softly, alighting on the houses of men. They stirred, waking from sleep, troubled by the heated air.” p. 136

“SUNDAY was dedicated to the mystery of the Holy Trinity, Monday to the Holy Ghost, Tuesday to the Guardian Angels, Wednesday to Saint Joseph, Thursday to the Most Blessed Sacrament of the Altar, Friday to the Suffering Jesus, Saturday to the Blessed Virgin Mary.” p. 141

“the three theological virtues, in faith in the Father Who had created him, in hope in the Son Who had redeemed him, and in love of the Holy Ghost Who had sanctified him;” p. 142

“Frequent and violent temptations were a proof that the citadel of the soul; had not fallen and that the devil raged to make it fall.” p. 147

“Some of the boys had then asked the priest if Victor Hugo were not the greatest French writer. The priest had answered that Victor Hugo had never written half so well when he had turned against the church as he had written when he was a catholic.” p. 150

“He had seen himself, a young and silentmannered priest, entering a confessional swiftly, ascending the altarsteps, incensing, genuflecting, accomplishing the vague acts of the priesthood which pleased him by reason of their semblance of reality and of their distance from it.” p. 152

Dieric Bouts,the older. At The Church of Saint Peter, Leuven, Belgium. Created: 1464 – 1467. Via Wikimedia.

“the order of Melchisedec.” p. 153

*****”He drew forth a phrase from his treasure and spoke it softly to himself:

-A day of dapled seaborne clouds.-

The phrase and the day and the scene harmonised in a chord. Words. Was it their colours? He allowed them to glow and fade, hue after hue: sunrise gold, the russet and green of apple orchards, azure of waves, the grey-fringed fleece of clouds. No, it was not their colours: it was the pose and balance of the period.” p. 160

askance

***”They were voyaging across the deserts of the sky, a host of nomads on the march, voyaging high over Ireland, westward bound. The Europe they had come from lay out there beyond the Irish Sea, Europe of strange tongues and valleyed and woodbegirt and citadelled and of entrenched and marshalled races.” p. 161

John Everett Millais – National Portrait Gallery. Via Wikimedia.

“His morning walk across the city had begun; and he foreknew that as he passed the sloblands of Fairview he would think of the cloistral silverveined prose of Newman; that as he walked along the North Strand Road, glancing idly at the windows of the provision ships, he would recall the dark humour of Guido Cavalcanti and smile; that as he went by Baird’s stone cutting works in Talbot Place the spirit of Ibsen would blow though him like a keen wind, a spirit of wayward boyish beauty;”p. 170

“His mind when wearied of its search for the essence of beauty amid the spectral words of Aristotle or Aquinas turned often for its pleasure to the dainty songs of the Elizabethans.” p. 170

“His thinking was a dusk of doubt and selfmistrust, lit up at moments by the lightnings of so clear a splendour that in those moments the world perished about his feet as if it had been fire consumed: and thereafter his tongue grew heavy and he met the eyes of others with unanswering eyes for he felt that the spirit of beauty had folded him round like a mantle and that in reveie at least he had been acquainted with nobility.” p. 171

“he had tried to peer into the social life of the city of cities through the words implere ollam denariorum which the rector had rendered sonorously as the filling of a pot with denaries.” p. 174

“but yet it wounded him to think that he would never be but a shy guest at the feast of the world’s culture and that the monkish learning, in terms of which he was striving to forge out an esthetic philosophy, was held no higher by the age he lived in than the subtle and curious jargons of heraldry and falconry.” p. 174

“the droll statue of the national poet of Ireland.” p. 174

“-Aquinas-answered Stephen-says pulcra sunt quæ visa placent.-” p. 180

“-In so far as it is apprehended by the sight, which I suppose means here esthetic intellection, it will be beautiful. But Aquinas also says Bonum est in quod tendit appetitus. In so far as it satisfies the animal craving for warmth fire is a good. In hell, however, it is an evil.-” p. 180

Nineteenth century Photochrom postcard of the Cliffs of Moher in County Clare in Ireland showing cliffside table and refreshments. Via Wikimedia.

“-These questions are very profound, Mr Dedalus-said the dean.-It is like looking down from the cliffs of Moher into the depth. Many go down into the depths and never come up. Only the trained diver can go down into those depths and explore them and come to the surface again.-” p. 181

“You know Epictetus?-

-An old gentleman-said Stephen coarsely-who said that the soul is very like a bucketful of water.-

-He tells us in his homely way-the dean went on-that he put an iron lamp before a statue of one of the gods and that a thief stole the lamp. What did the philosopher do? He reflected that it was in the character of a thief to steal and determined to buy and earthen lamp next day instead of the iron lamp.-” p. 181

“whether words are being used according to the literary tradition or according to the tradition of the marketplace. I remember a sentence of Newman’s, in which he says of the Blessed Virgin that she was detained in the full company of the saints. The use of the word in the marketplace is quite different. I hope I am not detaining you.-” p. 182

“That?-said Stephen.-Is that called a funnel? Is it not a tundish?-” p. 182

“-And to distinguish between the beautiful and the sublime-the dean added-to distinguish between moral beauty and material beauty. And to inquire what kind of beauty is proper to each of the various arts.” p. 184

“-In pursuing these speculations-said the dean conclusively-there is, however, the danger of perishing of inanition.” p. 184

The British Library – Image taken from page 274 of ‘Finland in the Nineteenth Century: by Finnish authors. Illustrated by Finnish artists. Via Wikimedia.

“-I may not have his talent-said Stephen quietly.

-You never know-said the dean brightly.-We never can say what is in us. I most certainly should not be despondent. Per aspera ad astra.-“

—

“The sentence of Saint James which says that he who offends against one commandment becomes guilty of all had seemed to him first a swollen phrase until he had began to grope in the darkness of his own state. From the evil seed of lust all other deadly sins had spring forth: pride in himself and contempt of others, covetousness in using money for the purchase of unlawful pleasures, envy of those whose vices he could not reach to and calumnious murmuring against the pious, gluttonous enjoyment of food, the dull glowering anger amid which he brooded upon his longing, the swamp of spiritual and bodily sloth in which his whole being had sunk.” p. 100

Francis Xavier

“the apostle of the Indies.” p. 102

Ignatius of Loyola

“A retreat, my dear boys, signifies a withdrawal for a while form the cares of our life, the cares of this workaday world, in order to examine the state of our conscience, to reflect on the mysteries of holy religion and to understand better why we are here in this world.” p. 104

“What doth it profit a man to gain the whole world if he suffer the loss of his immortal soul? Ah, my dead boys, believe me there is nothing in this wretched world that can make up for such a loss.” p. 104

“Banish from your minds all worldly thoughts, and think only of the last things, death, judgment, hell and heaven. He who remembers these things, says, Ecclesiastes, shall not sin for ever. He who remembers the last things will act and think with them always before his eyes.” p. 105

“What did it avail then to have been a great emperor, a great general, a marvellous inventor, the most learned of the learned? All were as on before the judgment seat of God.” p. 107

“The stars of heaven were falling upon the earth like the figs cast by the figtree which the wind has shaken. The sun, the great luminary of the universe, had become as sackcloth of hair. The moon was blood red. The firmament was a scroll rolled away. The archangel Michael, the prince of the heavenly host, appeared glorious and terrible against the sky. With one foot on the sea and one foot on the land he blew from the archangelical trumpet the brazen death of time. The three blasts of the angel filled all the universe. Time is, time was, but time shall be no more. At the last blast the souls of universal humanity throng towards the valley of Jehosaphat, rich and poor, gentle and simple, wise and foolish, good and wicked.” p. 107

Valley of Josaphat

Absalom

“O you who present a smooth smiling face to the world while your soul within is a foul swamp of sin, how will it fare with you in that terrible day?” p. 108

“Death is the end of us all. Death and judgement, brought into the world by the sin of our first parents, are the dark portals that close our earthly existence, the portals that open into the unknown and the unseen, portals through which every soul must pass, alone, unaided save by its good works, without friend or brother or parent or master to help it, alone and trembling.” p. 108

“Theologians consider that it was the sin of pride, the sinful thought conceived in an instant: non serviam: I will not serve. That instant was his ruin. He offended the majesty of God by the sinful thought of one instant and God cast him out of heaven into hell for ever.” p. 111

“Adam and Eve were then created by God and placed in Eden, in the plain of Damascus, that lovely garden resplendent with sunlight and colour, teeming with luxuriant vegetation. The fruitful earth gave them her bounty: beasts and birds were their willing servants: they knew not the ills our flesh is heir to, disease and poverty and death: all that a great and generous God could do for them was done.” p. 112

“-Alas, my dear little boys, they too fell. The devil, once a shining angel, a son of the morning, now a foul fiend came n the shape of a serpent, the subtlest of all the beasts of the field. He envied them. He, the fallen great one, could not bear to think that man, a being of clay, should possess the inheritance which he by his sin had forfeited for ever.” p. 112

“the damned are so utterly bound and helpless that, as a blessed saint, Saint Anselm, writes in his book on Similitudes, they are not even able to remove from the eye a worm that gnaws it.” p. 114

“-They lie in exterior darkness. For, remember, the fire of hell gives forth no light. As, as the command of God, the fire of the Babylonian furnance lost its heat by not its light so, at the command of God, the fire of hell, while retaining the intensity of its heat, burns eternally in darkness. It is a neverending storm of darkness, dark flames and dark smoke of burning brimstone, amid which the bodies are heaped one upon another without even a glimpse of air. Of all the plagues with which the land of the Pharaohs was smitten one plague alone, that of darkness, was called horrible.” p. 114

” And then imagine this sickening stench, multiplied a millionfold and a millionfold again from the millions upon millions of fetid carcasses massed together in the reeking darkness, a huge and rotting human fungus. Imagine all this and you will have some idea of the horror of the stench of hell.” p. 115

“Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire which was prepared for the devil and his angels!-” p. 118

“He passed up the staircase and into the corridor along the walls of which the overcoats and waterproofs hung like gibbeted malefactors, headless and dripping and shapeless. And at every step he feared that he had already died, that his soul had been wrenched forth of the sheath of his body, that he was plunging headlong though space.” p. 118

“The English lesson began with the hearing of the history. Royal persons, favourites, intriguers, bishops, passed like mute phantoms behind their veil of names. All had died: all had been judged. What did it profit a man to gain the whole world if he lost his soul? At last he had understood: and human life lay around him, a plain of peace whereon antilike men laboured in brotherhood, their dead sleeping under quiet mounds.” p. 119-120

“-Sin, remember, is a twofold enormity. It is a base conssent to the promptings of our corrupt nature to the lower instincts, to that which is gross and beastlike; and it is also a turning awat from the counsel of our higher nature, from all that is pure and holy, from the Holy God Himself. For this reason mortal sin is punished in hell by two different forms of punishment, physical and spiritual.” p. 121

***”Now imagine a mountain of sand, a million miles high, reaching from the earth to the farthest heavens, and a million miles broad, extending to remotest space, and a million miles in thickness: and imagine such an enormous mass of countless particles of sand multiplied as often as there are leaves in the forest, drops of water in the mighty ocean, feathers on birds, scales on fish, hairs on animals, atoms in the vast expanse of the air: and imagine that as the end of every million years a little bird came to that mountain and carried away in its beak a tiny grain of that sand. How many millions upon millions of centuries would pass before that bird had carried away even a square foot of that mountain, how many eons upon eons of ages before it had carried away all. Yet at the end of that immense stretch of time not even one instant of eternity could be said to have ended; even then, at the end of such a period, after that eon of time the mere thought of which makes our very brain reel dizzily, eternity would have scarcely begun.” p. 125-126

“The ticking went on unceasingly; and it seemed to this saint that the sound of the ticking was the ceaseless repetition of the words; ever, never. Ever to be in hell, never to be in heaven; ever to be shut off from the presence of God, never to be shut off from the presence of God, never to enjoy the beatific vision; ever to be eaten with flames, gnawed by vermin, goaded with burning spikes,” p. 126

“-As sin, an instant of rebellious pride of the intellect, made Lucifer and a third part of the cohorts of angels fall from their glory.” p. 127-128.

“Et ignotas animum dimittit in artes.” OVID, Metamorphoses, VIII., 18. (And he sets his mind to unknown arts) p. 1

“Then he heard the noise of the refectory every time he opened the flaps of his ears. It made a roar like a train at night. And when he closed the flaps the roar was shut off like a train going into a tunnel.” p. 7

“-Tell us, Dedalus, do you kiss your mother before you go to bed? Stephen answered:

-I do.

Wells turned to the other fellows and said:

-O, I say, here’s a fellow says he kisses his mother every night before he goes to bed.

The other fellows stopped their game and turned round, laughing. Stephen blushed under their eyes and said:

-I do not.

Wells said:

-O, I say, here’s a fellow says he doesn’t kiss his mother before he goes to bed.

They all laughed again. Stephen tried to laugh with them. He felt his whole body hot and confused in a moment. What was the right answer to the question?” p. 8

“But the Christmas vacation was very far away: but one time it would come because the earth moved round always.” p. 9

“There was a picture of the earth on the first page of his geography: a big ball in the middle of clouds. Fleming had a box of crayons and one night during free study he had coloured the earth green and the clouds maroon.” p. 9

“He turned to the flyleaf of the geography and read what he had written there: himself, his name and where he was.

Stephen Dedalus

Class of Elements

Clongowes Wood College

Sallins

County Kildare

Ireland

Europe

The World

The Universe” p. 10

“What was after the universe? Nothing. But was there anything round the universe? Nothing. But was there anything round the universe to show where it stopped before the nothing place began? It could not be a wall but there could be a thin thin line there all round everything. It was very big to think about everything and everywhere. Only God could do that.” p. 10

“The corridors were darkly lit and the chapel was darkly lit. Soon all would be dark and sleeping. There was cold night air in the chapel and the marbles were the colour the sea was at night. The sea was cold day and night: but it was colder at night.” p. 12

“It would be lovely to sleep for one night in that cottage before the fire of smoking turf, in the dark lit by there fire, in the warm dark, breathing the smell of the peasants, air and rain and turf and corduroy. But, O, the road there between the trees was dark! You would be lost in the dark. It made him afraid to think of how it was.” p. 12

“The prefect’s shoes went away. Where? Down the staircase and along the corridors or to his room at the end? He saw the dark. Was it true about the black dog that walked there at night with eyes as big as carriagelamps? They said it was the ghost of a murderer. A long shiver of fear flowed over his body. He saw the dark entrance hall of the castle.” p. 13

“And the train raced on over the flat lands and past the Hill of Allen. The telegraph poles were passing, passing. The train went on and on. It knew. There were lanterns in the hall of his father’s house and ropes of green branches.” p. 14-15

***”Every rat had two eyes to look out of. Sleek slimy coats, little little feet tucked up to jump, black slimy eyes to look out of. They could understand how to jump. But the minds of rats could not understand trigonometry. When they were dead they lay on their sides. Their coats dried then. They were only dead things.” p. 16

“How pale the light was at the window! But that was nice. There fire rose and fell on the wall. It was like waves. Someone had put coal on and he heard voices. They were talking. It was the noise of waves. Or the waves were talking among themselves as they rose and fell.

He saw the sea of waves, long dark waves rising and falling, dark under the moonless night. A tiny light twinkled at the pierhead where the ship was entering: and he saw a multitude of people fathered by the water’s edge to see the ship that was entering their harbour.” p. 21

“Perhaps they had stolen a monstrance to run away with it and sell it somewhere. That must have been a terrible sin, to go in there quietly at night, to open the dark press and steal the flashing gold thing into which God was put on the altar in the middle of flowers and candles at benediction while the incense went up in clouds at both sides as the fellow swung the censer and Dominic Kelly sang the first part by himself in the choir. But God was not in it of course when they stole it. But still it was a strange and a great sin even to touch it.” . 40

“The word was beautiful: wine. It made you think of dark purple because the grapes were dark purple that grew in Greece outside houses like white temples. But the faint smell off the rector’s breath had made him feel a sick feeling on the morning of his first communion.” p. 41

“-Where did you break your glasses? repeated the prefect of studies.

-The cinderpath, sir.

-Hoho! The cinderpath! cried the prefect of studies. I know that trick.

Stephen lifted his eyes in wonder and saw for a moment Father Dolan’s whitegrey not young face, his baldy whitegray head with fluff at the sides of it, the steel rims of his spectacles and his no-coloured eyes looking through the glasses. Why did he say he knew that trick?

-Lazy idle little loafer! cried the prefect of studies. Broke my glasses! An old schoolboy trick! Out with your hand this moment!” p. 44

“A hot burning stinging tingling blow like the loud crack of a broken stick made his trembling hand crumple together like a leaf in the fire” p. 44

“Stephen knelt down quickly pressing his beaten hands to his sides. To think of them beaten and swollen with pain all in a moment made him feel so sorry for them as if they were not his own but someone else’s that he felt sorry for.” p. 45

“He saw the rector sitting at a desk writing. There was a skull on the desk and a strange solemn smell in the room like the old leather of chairs.

His heart was beating fast on account of the solemn place he was in and the silence of the room: and he looked at the skull and at the rector’s kind-looking face.” p. 50

“He would be very quiet and obedient: and he wished that he could do something kind for him to show him that he was not proud.” p. 53

“Stephen knelt at his side respecting, though he did not share, his piety. He often wondered what his granduncle prayed for so seriously. Perhaps he prayed for the souls in purgatory or for the grace of a happy death or perhaps he prayed that God might send him back a part of the big fortune he had squandered in Cork.” p. 56

“Trudging along the road or standing in some grimy wayside public house his elders spoke constantly of the subjects nearer their hearts, of Irish politics, of Munster and of the legends of their own family, to all of which Stephen lent an avid ear.” p. 56

“The hour when he too would take part in the life of that world seemed drawing near and in secret he began to make ready for the great part which he felt awaited him there nature of which he only dimly apprehended.

His evenings were his own; and he pored over a ragged translation of The Count of Monte Cristo. The figure of that dark avenger stood forth in his mind for whatever he had heard or divined in childhood of the strange and terrible.” p. 56

“Outside Blackrock, on the road that led to the mountains, stood a small whitewashed house in the garden of which grew many rosebushes: and in this house, he told himself, another Mercedes lived. Both on the outward and on the homeward journey he measured distance by this landmark: and in his imagination he lived through a long train of adventures, marvellous as those in the book itself, towards the close of which there appeared an image of himself, grown older and sadder, standing in a moonlit garden with Mercedes who had so many years before slighted his love, and with a sadly proud gesture of refusal, saying:

-Madam, I never eat muscatel grapes.” p. 57

Dantès sur son rocher, affiche de Paul Gavarni pour Monte Cristo d’Alexandre Dumas. 1846.

“He passed unchallenged among the docks and along the quays wondering at the multitude of corks that lay bobbing on the surface of the water in a thick yellow scum, at the crowds of quay porters and the rumbling carts and the ill dressed bearded policemen. The vastness and strangeness of the life suggested to him by the bales of merchandise stocked along the walls or swung aloft out of the holds of streamers wakened again in him the unrest which had sent him wandering in the evening from garden to garden in search of Mercedes.” p. 60-61

“He sat listening to the words and following the ways of adventure that lay open in the coals, arches and vaults and winding galleries and jagged caverns.

Suddenly he became aware of something in the doorway. A skull appeared suspended in the gloom of the doorway. A feeble creature like a monkey was there, drawn there by the sound of voices at the fire. A whining voice came from the door asking:

-Is that Josephine?” p. 62

The Bride of Abydos or Selim and Zuleika. Painting, 1857, by Eugène Delacroix depicting Lord Byron’s work.

“The light spread upwards from the glass roof making the theatre seem a festive ark, anchored among the hulks of houses, her frail cables of lanterns looping her to her moorings.” p. 69

“Then a noise like dwarf artillery broke the movement. It was the clapping that greeted the entry of the dumb bell team on the stage.” p. 69

“Stephen shook his head and smiled in his rival’s flushed and mobile face, beaked like a bird’s. He had often thought it strange that Vincent Heron had a bird’s face as well as a bird’s name.” p. 70

“-Here. It’s about the Creator and the soul. Rrm… rrm…rrm…Ah! without a possibility of ever approaching nearer. That’s heresy.

Stephen murmured:

-I mean without a possibility of ever reaching.

It was a submission and Mr Tate, appeased, folded up the essay and passed it across to him, saying:

-O…Ah! ever reaching. That’s another story.

But the class was not so soon appeased. Though nobody spoke to him of the affair after class he could feel about him a vague general malignant joy.” p. 73

“As soon as the boys had turned into Clonliffe Road together they began to speak about books and writers, saying what books they were reading and how many books there were in their father’s bookcases at home. Stephen listened to them in some wonderment for Boland was the dunce and Nash the idler of the class. In fact after some talk about their favourite writers Nash declared for Captain Marryat who, he said, was the greatest writer.

-Fudge! said Heron. Ask Dedalus. Who is the greatest writer, Dedalus?

Stephen noted the mockery in the question and said:

-Of prose do you mean?

-Yes.

-Newman, I think.

-Is it Cardinal Newman? asked Boland.

-Yes, answered Stephen.” p. 74

“-Admit that Byron was no good.

-No.

-Admit.

-No.

-Admit.

-No. No.

At lasty after a fury of plunges he wrenched himself free. His tormentors set off towards Jone’s Road, laughing and jeering at him, while he, half blinded with tears, stumbled on, clenching his fists madly and sobbing.” p. 76

“While his mind had been pursuing its intangible phantoms and turning in irresolution from such pursuit he had heard about him the constant voices of his father and of his masters, urging him to be a gentleman above all things and urging him to be a good catholic above all things. These voices had now come to be hollow sounding in his ears.” p. 77

“He gave them ear only for a time but he was happy only when he was far from them, beyond their call, alone or in the company of phantasmal comrades.” p. 78

“He stood still and gazed up at the sombre porch of the morgue and from that to the dark cobbled laneway at its side.” p. 80

“-That is hose piss and rotted straw, he thought. It is a good odour to breathe. It will calm my heart. My heart is quite calm now. I will go back.” p. 80

****”As the train steamed out of the station he recalled his childish wonder of years before and every event of his first day at Clongowes. But he felt no wonder now. He saw the darkening lands slipping away past him, the silent telegraphpoles passing his window swiftly every four seconds, the little glimmering stations, manned by a few silent sentries, flung by the mail behind her and twinkling for a moment in the darkness like fiery grains flung backwards by a runner.” p. 81

“He listened without sumpathy to his father;s evocation of Cork and of scenes of his youth-a tale broken by sighs or draughts from his pocket flask whenever the image of some dead friend appeared in it, or whenever the evoker remembered suddenly the purpose of his actual visit.” p. 81

“They drove in a jingle across Cork while it was still early morning and Stephen finished his sleep in a bedroom of the Victorian Hotel.” p. 81

“His father was standing before the dressingtable, examining his hair and face and moustache with great care, craning his neck across the water jug and drawing it back sideways to see the better. While he did so he sang softly to himself with quaint accent and phrasing:

“‘Tis youth and folly

Makes young men marry,”” p. 82

“The consciousness of the warm sunny city outside his window and the tender tremors with which his father’s voice festooned the strange sad happy air, drove off all the mists of the night’s ill humour from Stephen’s brain.” p. 82

“Then he had been sent away from home to a college, he had made his first communion and eaten slim jim out of his cricket cap and watched the firelight leaping and dancing on the wall of a little bedroom in the infirmary and dreamed of being dead, of mass being said for him by the rector in a black and gold cope, of being buried then in the little graveyard of the community off the main avenue of lines. But he had not died then. Parnell had died.” p. 86-87

“His mind seemed older than theirs: it shone coldly on their strifes and happiness and regrets like a moon upon a younger earth. No life or youth stirred in him as it had stirred in them.” p. 89

“His childhood was dead or lost and with it his soul capable of simple joys and he was drifting amid life like the barren shell of the moon.

“Art thou pale for weariness

Of climbing heaven and gazing on the earth,

Wandering companionless?…” p. 89

Louis Édouard Fournier, The Cremation of Percy Bysshe Shelley, oil on canvas, Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery. Louis Édouard Fournier (1857-1917). Via Wikimedia.

“My old professor, meanwhile, was stunned by the normalcy of the day around him. Shouldn’t the world stop? Don’t they know what has happened to me?

But the world did not stop, it took no notice at all,” p. 8

“Do I wither up and disappear, or do I make the best of my time left?” p. 10

Don’t assume that it’s too late to get involved.” p. 18

“I decided I’m going to live-or at least try to live-the way I want, with dignity, with courage, with humor, with composure.” p. 21

“There are some mornings when I cry and cry and mourn for myself. Some mornings, I’m so angry and bitter. But it doesn’t last too long. Then I get up and say, ‘I want to live…'” p. 21

“I had become too wrapped up in the siren song of my own life. I was busy.” p. 33

“And you have to be strong enough to say if the culture doesn’t work, don’t buy it. Create your own. Most people can’t do it. They’re more unhappy than me-even in my current position.” p. 35-36

“You take certain things for granted, even when you know you should never take anything for granted.” p. 40

“they gave up days and weeks of their lives, addicted to someone else’s drama.” p. 42

“He read books to find new ideas for his classes, visited with colleagues, kept up with old students, wrote letters to distant friends.” p. 42

“conversation, interaction, affection-and it filled his life like an overflowing soup bowl.” p. 43

“So many people walk around with a meaningless life. They seem half-asleep, even when they’re busy doing things they think are important. This is because they’re chasing the wrong things. The way you get meaning into your life is to devote yourself to loving others, devote yourself to your community around you, and devote yourself to creating something that gives you purpose and meaning.” p. 43

“The most important thing in life is to learn how to give out love, and to let it come in.” p. 52

“Why are we embarrassed by silence? What comfort do we find in all the noise?” p. 53

“I give myself a good cry if I need it. But then I concentrate on all the good things still in my life. On the people who are coming to see me. On the stories I’m going to hear.” p. 57

“the culture doesn’t encourage you to think about such things until you’re about to die. We’re so wrapped up with egotistical things, career, family, having enough money, meeting the mortgage, getting a new car, fixing the radiator when it breaks-we’re involved in trillions of little acts just to keep going. So we don;t get into the habit of standing back and looking at our lives and saying, Is this all? Is this all I want? Is something missing?” p. 64-65

“A teacher affects eternity; he can never tell where his influence stops.” Henry Adams. p. 79

*****”Everybody knows they’re doing to die… but nobody believes it. If we did, we would do things differently… To know you’re going to die, and to be prepared for it at any time. That’s better. That way you can actually be more involved in your life while you’re living… Do what the Buddhists do. Every day, have a little bird on your shoulder that asks, ‘Is today the day? Am I being the person I want to be?'” p. 81

“once your learn how to die, you learn how to live.” p. 82

“most of us all walk around as if we’re sleepwalking. We really don’t experience the world fully, because we’re half-asleep, doing things we automatically think we have to do.” p. 83

“if you really listen to that bird on your shoulder, if you accept that you can die at any time-then you might not be as ambitious as you are.” p. 83

“We are too involved in materialistic things, and they don’t satisfy us. The loving relationships we have, the universe around us, we take these things for granted.” p. 84

“If you don’t have the support and love and caring and concern that you get from a family, you don’t have much at all.” p. 91

“‘spiritual security’-knowing that your family will be there watching our for you. Nothing else will give you that. Not money. Not fame.” p. 92

“If you want the experience of having complete responsibility for another human being, and to learn how to love and bond in the deepest way, then you should have children.” p. 93

“I dove into work. I worked because I could control it. I worked because work was sensible and responsive.” p. 96

“Learn to detach.” p. 103

“But once he recognized the feel of those emotions, their texture, their moisture… the quick flash of heat that crosses your brain-then he was able to say, “Okay. This is fear. Step away from it. Step away.” p. 104-105

“There is a tribe in the North American Arctic, for example, who believe that all things on earth have a soul that exists in a miniature form of the body that holds it-so that a deer has a tiny deer inside it, and a man has a tiny man inside him. When the being dies, that tiny form lives on. It can slide into something being born nearby, or it can go to a temporary resting place in the sky, in the belly of a great feminine spirit, where it waits until the moon can send it back to earth.” p. 114

“Aging is not just decay, you know. It’s growth. It’s more than the negative that you’re going to die, it’s also the positive that you understand you’re going to die, and that you live better because of it.” p. 118

“All younger people should know something. If you’re always battling against getting older, you’re always going to be unhappy, because it will happen anyhow.” p. 118-119

“Remember what I said about detachment? Let it go. Tell yourself, ‘That’s envy. I’m going to separate from it now.’ And walk away.” p. 119

“The truth is, part of me is every age. I’m a three-year-old, I’m a five-year-old, I’m a thirty-seven-year old, I’m a fifty-year-old. I’ve been through all of them, and I know what it’s like. I delight in being a child when it’s appropriate to be a child. I delight in being a wise old man when it’s appropriate to be a wise old man.” p. 120

“Devote yourself to loving others, devote yourself to your community around you, and devote yourself to creating something that gives you purpose and meaning.” p. 127

****”if you’re trying to show off for people at the top, forget it. They will look down at you anyhow. And if you’re trying to show off for people at the bottom,forget it. They will only envy you. Status will get you nowhere.” p. 127

“Do the kinds of things that come from the heart. When you do, you won’t be dissatisfied, you won’t be envious, you won’t be longing for somebody else’s things. On the contrary, you’ll be overwhelmed with what comes back.” p. 128

“Each night, when I go to sleep, I die. And the next morning when I wake up, I am reborn.” Mahatma Ghandi p. 129

“When Morrie was with you, he was really with you. He looked you straight in the eye, and he listened as if you were the only person in the world.” p. 135

“I believe in being fully present… That means you should be with the person you’re with. When I’m talking to you now, Mitch, I try to keep focused only on what is going on between us. I am not thinking about something we said last week.” p. 135

“So many people with far smaller problems are so self-absorbed, their eyes glaze over if you speak for more than thirty seconds. They already have something else in mind” p. 136

“People haven’t found meaning in their lives, so they’re running all the time looking for it. They think the next car, the next house, the next job. Then they find those things are empty, too, and they keep running.” p. 136

“I don’t put have to be in that much of a hurry with my car. I would rather put my energies into people.” p. 137

“love and marriage: If you don’t respect the other person, you’re gonna have a lot of trouble. If you don’t know how to compromise, you’re gonna have a lot of trouble. If you can’t talk openly about what does on between you, you’re gonna have a lot of trouble. And if you don’t have a common set of values in life, you’re gonna have a lot of trouble. Your values must be alike.” p. 149

“People are only mean when they’re threatened… and that’s what our culture does.” p. 154

“The little things, I can obey. But the big things-how we think, what we value-those you must choose yourself. You can’t let anyone-or any society-determine those for you.” p. 155

“the biggest defect we human beings have is our shortsightedness.” p. 156

“Invest in the human family. Invest in people.” p. 157

“this disease is knocking at my spirit. But it will not get my spirit. It’ll get my body. It will not get my spirit.” p. 163

“There is no point in keeping vengeance or stubbornness… these things I so regret in my life. Pride. Vanity.” p. 164

“I mourn my dwindling time, but I cherish the chance it gives me to make things right.” p. 167

“Make peace with living.” p. 173

“Death ends a life, not a relationship.” p. 174

“how could he find perfection in such an average day.” p. 176

“There is no formula to relationships. They have to be negotiated in loving ways, with room for both parties, what they want and what they need, what they can do and what their life is like.” p. 177-178

“We’re all going to crash! All of us waves are going to be nothing! Isn’t it terrible?’

“The second wave says, ‘No, you don’t understand. You’re not a wave, you’re part of the ocean.” p. 179-180

“My father moved through theys of we,

singing each new leaf out of each tree

(and every child was sure that spring

danced when she heard my father sing)…”

“I want to tell him to be more open, to ignore the lure of advertised values, to pay attention when your loved ones are speaking, as if it were the last time you might hear them.” p. 192

“But if Professor Morris Schwartz taught me anything at all, it was this: there is no such thing as “too late” in life. He was changing until the day he said good-bye.” p. 190

“Or the discovery of a demented and glacial universe where to be in-human was human, where disciplined, educated men in uniform came to kill, and innocent children and weary old men came to die?” p ix

“We believed in God, trusted in man, and lived with the illusion that every one of us has been entrusted with a sacred spark from the Shekhinah’s flame; that every one of us carries in his eyes and in his soul a reflection of God’s image.” p. x-xi

“To forget would be not only dangerous but offensive; to forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.” p. xv

Moishe the Beadle “He spoke little. He sang, or rather he chanted, and the few snatches I caught here and there spoke of divine suffering, of the Shekhinah in Exile, where according to Kabbalah, it awaits its redemption linked to that of man.” p. 3

“One day I asked my father to find me a master who could guide me in my studies of Kabbalah. “You are too young for that. Maimonides tells us that one must be thirty before venturing into the world of mysticism, a world fraught with peril. First you must study the basic subjects, those you are able to comprehend.” p. 4

Moses Maimonides. Blaisio Ugolino. 1744. Via wikimedia.

Moishe “explained to me, with great emphasis, that every question possessed a power that was lost in the answer…” p. 4-5.

“Man comes closer to God thought the questions he asks Him, he liked to say. Therein lies true dialogue. Man asks and God replies. But we don’t understand His replies. We cannot understand them. Because they dwell in the depths of our souls and remain there until we die. The real answers, Eliezer, you will find only within yourself.” p. 5

“There are a thousand and one gates allowing entry into the orchard of mystical truth. Every human being has his own gate. He must not err and wish to enter the orchard through a gate other than his own.” p. 5

“In front of us, those flames. In the air, the smell of burning flesh. It must have been around midnight. We had arrived. In Birkenau.” p. 28

“I didn’t know this was the moment in time and the place where I was leaving my mother and Tzipora forever. I kept walking, my father holding my hand.” p. 29

“NEVER SHALL I FORGET that night, the first night in camp, that turned my life into one long night seven times sealed.

Never shall I forget that smoke.

Never shall I forget the small faces of the children whose bodies I saw transformed into smoke under a silent sky.

Never shall I forget those flames that consumed my faith forever.

Never shall I forget the nocturnal silence that deprived me for all eternity of the desire to live.

Never shall I forget those moments that murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to ashes.

Never shall I forget those things, even were I condemned to live as long as God Himself.

Never.” p. 34

“But no sooner had we taken a few more steps than we saw the barbed wire of another camp. This one had an iron gate with the overhead inscription: ARBEIT MACHT FREI. Work makes you free.

Auschwitz.” p. 40

“Have faith in life, a thousand times faith. By driving out despair, you will move away from death. Hell does not last forever…” p. 41

“But there were those who said we should fast, precisely because it was dangerous to do so. We needed to show God that even here, locked in hell, we were capable of singing His praises.” p. 69

“”Perhaps someone here has seen my son?”

He had lost his son in the commotion. He had searched for him among the dying, to no avail. Then he had dug through the snow to find his body. In vain.” p. 90

“”No, Rabbi Eliahu, I haven’t seen him.”

And so he left, as he had come: a shadow swept away by the wind.” p. 91

“A terrible thought crossed my mind: What if he had wanted to be rid of his father? He had felt his father growing weaker and, believing that the end was near, had thought by this separation to free himself of a burden that could diminish his own chance for survival… “Oh God, Master of the Universe, give me the strength never to do what Rabbi Eliahu’s son has done.” p. 91

“When at last a grayinsh light appeared on the horizon, it revealed a tangle of human shapes, heads sunk deeply between shoulders, crouching, piled one on top of the other, like a cemetery covered with snow. In the early dawn light, I tried to distinguish between the living and those who were no more. But there was barely a difference.” p. 98

“I gave him what was left of my soup. But my heart was heavy. I was aware that I was doing it grudgingly.

Just like Rabbi Eliahu’s son, I had not passed the test.” p. 107

“All of a sudden, he sat up and placed his feverish lips against my ear:

“Eliezer… I must tell you where I buried the gold and silver…In the cellar… You know…”” p. 108

“No prayers were said over his tomb. No candle lit in his memory. His last word had been my name. He had called out to me and I had not answered.” p. 112

“I had not seen myself since the ghetto.

From the depth of the mirror, a corpse was contemplating me.” p. 115

Nobel Peace Prize Acceptance Speech

“Because if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices.” p. 118

“We must take sides Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When himan lives are endangered, when himan dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant.” p. 118

“Nobody under the bed; nobody in the closet; nobody in his dressing-gown, which was hanging up in a suspicious attitude against the wall.” p. 12

“”Business cried the Ghost, wringing its hands again. “Mankind was by business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business.!”” p. 17

“Why did I walk through crowds of fellow-beings with my eyes turned down, and never raise them to that blessed Star which led the Wise Men to a poor adobe?”p. 17

“The apparition walked backward from him; and at every step it took, the window raised itself a little, so that when the spectre reached it, it was wide open.” p. 19

“The misery with them all was, clearly, that they sought to interfere, for good, in human matters, and had lost the power for ever.” p. 19

“They walked along the road; Scrooge recognising every gate, and post, and tree; until a little market-town appeared in the distance, with its bridge, its church, and winding river.” p. 25

“It opened before them, and disclosed a long, bare, melancholy room, made barer still by lines of plain deal forms and desks. At one of these a lonely boy was reading near a feeble fire; and Scrooge sat down upon a form, and wept to see his poor forgotten self as he had used to be.” p. 26

“”What Idol has displaced you?” he rejoined.

“A golden one.” p. 34

“If he be like to die, he had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.” p. 50

“It may be, that in the sight of Heaven, you are more worthless and less fit to live than millions like this poor man’s child. Oh God! to hear the Insect on the leaf pronouncing on the too much life among his hungry brothers in the dust!”” p. 50

“And now, without a word of warning from the Ghost, they stood upon a bleak and desert moor, where monstrous masses of rude stone were cast about, as though it were the burial-place of giants” p. 53

“Down in the west the setting sun had left a streak of fiery red, which glared upon the desolation for an instant, like a sullen eye, and frowning lower, lower, lower yet, was lost in the thich gloom of darkest night.” p. 53

“lifted his eyes, beheld a solemn Phantom, draped and hooded, coming, like a mist along the ground, towards him.” p. 62

“in the very air through which this Spirit moved it seemed to scatter gloom and mystery.” p. 63

“Secrets that few would like to scrutinise were bred and hidden in mountains of unseemly rags, masses of corrupted fat, and sepulchres of bones.” p. 67

“He thought, if this man could be raised up now, what would be his foremost thoughts? Avarice, hard dealing, griping cares? They have brought him to a rich end, truly!” p. 71

“A cat was tearing at the door, and there was a sound of gnawing rats beneath the hearth-stone. What they wanted in the room of death, and why they were so restless and disturbed, Scrooge did not dare to think.” p. 71

“Some people laughed to see the alteration in him, but he let them laugh, and little heeded them; for he was wise enough to know that nothing ever happened on this globe, for good, at which some people did not have their fill of laughter in the outset” p. 85

—

“Dickens spent considerable energy giving public readings of his own works.” p. 87

“The world is what it is; men who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it.” p. 3

“In the darkness of the river and forest you could be sure only of what you could see–made a noise–dipped a paddle in the water–you heard yourself as though you were another person. The river and the forest were like presences, and much more powerful than you.” p. 8

“Zabeth was a magician, and was known in our region as a magician. Her smell was he smell of her protecting ointments. Other women used perfumes and scents to attract; Zabeth’s ointments repelled and warned.” p. 10

“Without Europeans, I feel, all our past would have been washed away, like the scuff marks of fishermen on the beach outside our town.” p. 12

***”All that had happened in the past was washed away; there was always only the present. It was as though, as a result of some disturbance in the heavens, the early morning light was always receding into the darkness, and men lived in a perpetual dawn.” p. 12

“When things went wrong they had the consolations of religion. This wasn’t just a readiness to accept Fate; this was a quiet and profound conviction about the vanity of all human endeavour.” p. 16

“a relisher of life, a seeker after experience” p. 25

“I wondered about the nature of my aspirations, the very supports of my existence; and I began to feel that any life I might have anywhere–however rich and successful and better furnished–would only be a version of the life I lived now.” p. 42

**”Always, sailing up from the south, from beyond the bend in the river, were clumps of water hyacinths, dark floating islands on the dark river, bobbing over the rapids. It was as if rain and river were tearing away bush from the heart of the continent and floating it down to the ocean, incalculable miles away… Night and day the water hyacinth floated up from the south, seeding itself as if travelled.” p. 46

“They said they were poor and wanted money to continue their studies. Some of these beggars were bold, coming straight to me and reciting their requests; the shy ones hung around until there was no one else in the shop. Only a few had bothered to prepare stories, and these stories were like Ferdinand’s: a father dead or far away, a mother in a village, an unprotected boy full of ambition… The guilelessness, the innocence that wasn’t innocence–I thought it could be traced back to Ferdinand, his interpretation of our relationship and his idea of what I could be used for.” p. 55

“The people here were malins the way a dog chasing a lizard was malins because they lived with the knowledge of men as prey.” p. 56

“Every carving, every mask, served a specific religious purpose, and could only be made once. Copies were copies; there was no magical feeling or power in them; and in such copies Father Huismans was not interested. He looked in masks and carvings for a religious quality; without that quality the things were dead and without beauty.” p. 61

“The first Roman hero, travelling to Italy to found his city, lands on the coast of Africa. The local queen falls in love with him, and it seems that the journey to Italy might be called off. But then the watching gods take a hand; and one of them says that the great Roman god might not approved of a settlement in Africa, of a mingling of peoples there, of treaties of union between Africans and Romans.” p. 62

Dido and Aeneas, from a Roman fresco, Pompeian Third Style (10 BC – 45 AD), Pompeii, Italy. Via Wikimedia.

“This is Zabeth’s world. This is the world to which she returns when she leaves my shop. But Zabeth’s world was living, and this was dead. That was the effect of those masks lying flat on the shelves, looking up not forest or sky but at the underside of other shelves. They were masks that had been laid low, in more than one way, and had lost their power.” p. 65

“wandering back to the food stalls: little oily heaps of fried flying ants (expensive, and sold by the spoonful) laid out on scraps of newspaper; hairy orange-coloured caterpillars with protuberant eyes wriggling in enamel basins; fat white grubs kept moist and soft in little bags of damp earth, five or six grubs to a bag–these grubs, absorbent in body and of neutral taste, being an all-purpose fatty food, sweet with sweet things, savory with savory things. These were all forest foods, but the villages had been cleaned out of them (grubs came from the heart of a pal tree); and no one wanted to go foraging too far in the forest.” p. 66

“While he lived, Father Huismans, collecting the things of Africa, had been thought a friend of Africa. But now that changed. It was felt that the collection was an affront to African religion… The masks themselves, crumbling n the slatted shelves, seemed to lose the religious power Father Huismans had taught me to see in them; without him, they simply became extravagant objects.” p. 84

“It wasn’t the ice cream that attracted Mahesh. It was the idea of the simple machine, or rather the idea of being the only man in the town to own such a machine… They are dazzled by the machines they import. That is part of their intelligence; but they soon start behaving as though they don’t just own the machines, but the patents as well; they would like to be the only men in the world with such magical instruments.” p. 90

“They didn’t see, these young men, that there was anything to build in their country. As far as they were concerned, it was all there already. They had only to take. They believed that, by being what they were, they had earned the right to take; and the higher the officer, the greater the crookedness–if that word had any meaning.” p. 91

“It seemed as easy as that, if you came late to the world and found ready-made those things that other countries and peoples had taken so long to arrive at–writing, printing, universities, books, knowledge. The rest of us had to take thngs in stages. I thought of my own family, Nazruddin, myself–we were so clogged by what the centuries had deposited in our minds and hearts. Ferdinand, starting from nothing, had with one step made himself free, and was ready to race ahead of us.” p. 102-103

“We lived on the same patch of earth; we looked at the same views. Yet to him the world was new and getting newer. For me that same world was drab, without possibilities.” p. 103

“”Would the honourable visitor state whether he feels that Africans have been depersonalized by Christianity?”

¶Indar did what he had done before. He restated the question. He said, “I suppose you are really asking whether Africa can be served by a religion which is not African. Is Islam an African religion? Do you feel that Africans have been depersonalized by that?”” p. 121

“You are men of the modern world. Do you need African religion? Or are you being sentimental about it? Are you nervous of losing it? Or do you feel you have to hold on to it just because it’s yours?” p. 122

Raymond “I find that the most difficult thing in prose narrative is linking one thing with the other. The link might just be a sentence, or even a word. It sums up what has gone before and prepares one for what is to come.” p. 136

“There may be some parts of the world–dead countries, or secure and by-passed ones–where men can cherish the past and think of passing on furniture and china to their heirs. Men can do that perhaps in Sweden or Canada. Some peasant department of France full of half-wits in châteaux; some crumbling Indian palace-city, or some dead colonial town in a hopeless South American country. Everywhere else men are in movement, the world is in movement, and the past can only cause pain.” p. 141

“But I hadn’t understood to what extent our civilization had also been our prison. I hadn’t understood either to what extent we had been made by the place where we had grown up, made by Africa and the simple life of the coast, and how incapable we had become of understanding the outside world.” p. 142

“But this lady also thought that my education and background made me extraordinary,and I couldn’t fight the idea of my extraordinariness.

¶”An extraordinary man, a man of two worlds, needed an extraordinary job. And she suggested I become a diplomat.” p. 145

“there was the Edgware Road, where the shops and restaurants seemed continually to be changing hands; there were the shops and crowds of Oxford Street and Regent Street. The openness of Trafalgar Square gave me a lift, but it reminded me that I was almost at the end of my journey.” p. 146

“Now I saw differently. And I understood that London wasn’t simply a place that was there, as people say of mountains, but that it had been made by men, that men had given attention to details as minute as those camels.

¶I began to understand at the same time that my anguish about being a man adrift was false, that for me that dream of home and security was nothing more than a dream of isolation, anachronistic and stupid and very feeble. I belonged to myself alone.” p. 151

“We solace ourselves with that idea of the great men of our tribe, the Gandhi and the Nehru, and we castrate ourselves. ‘Here, take my manhood and invest it for me. Take my manhood and be a greater man yourself, for my sake!’ No! I want to be a man myself.” p. 152

“The job is thee, waiting. But it doesn’t exist for you or anyone else until you discover it, and you discover it because it’s for you and you alone.” p. 153

“These three people were in many ways alike–renegades, concerned with their personal beauty, finding in that beauty the easiest form of dignity.” p. 157

“Rustic manners, forest manners, in a setting not of the forest. But that was how, in our ancestral lands, we all began–the prayer may on the sand, then the marble floor of a mosque; the rituals and taboos of nomads, which transferred to the palace of a sultan or a maharaja, become the traditions of an aristocracy.” p. 161

“In spite of the corrupt physical ways our passion had begun to take, the photographs of Yvette that I preferred were the chastest. I was especially interested in those of her as a girl in Belgium, to whom the future was still a mystery.” p. 184

“The businessman bought at ten and was happy to get out at twelve; the mathematician saw his ten rise to eighteen, but didn’t sell because he wanted to double his ten to twenty.” p. 198

“Uganda was beautiful, fertile, easy, without poverty, and with high African traditions. It ought to have had a future, but the problem with Uganda was that it wasn’t big enough. The country was now too small for its tribal hatreds.” p. 200-201

Shoba and Mahesh “Acid on the face of the woman, the killing of the man–they were the standard family threats on these occasions,” p. 203

“”You can hire them, but you can’t buy them.” It was one of his sayings; it meant that stable relationships were not possible here, that there could only be day-to-day contracts between men, that in a crisis peace was something you had to buy afresh every day.” p. 210

“We came down slowly, leaving the upper light. Below the heavy cloud Africa showed as a dark-green, wet-looking land. You could see that it was barely dawn down there; in the forests and creeks it would still be quite dark.” p. 247

“The water hyacinths, “the new thing in the river,” beginning so far away, in the centre of the continent, bucked past in clumps and tangles and single vines, here almost at the end of their journey.” p. 249

“If there was a plan, these events had meaning. If there was law, these events had meaning. But there was no plan; there was no law; this was only make-believe, play, a waste of men’s time in the world. And how often here, even in the days of bush, it must have happened before, this game of warders and prisoners in which men could be destroyed for nothing. I remembered what Raymond used to say–about events being forgotten, lost, swallowed up.” p. 267

“The searchlight lit up the barge passengers, who, behind bars and wire guards, as yet scarcely seemed to understand that they were adrift. Then there were gunshots. The searchlight was turned off; the barge was no longer to be seen. The steamer started up again and moved without lights down the river, away from the area of battle. The air would have been full of moths and flying insects. The searchlight, while it was on, had shown thousands, white in the white light.

¶July 1977-August 1978” p. 278

“As the hours passed, the room, already dark, seemed to diminish around us, until it resembled a screening room, or a chapel, a place where questions of how to live are posed through stories and images.”

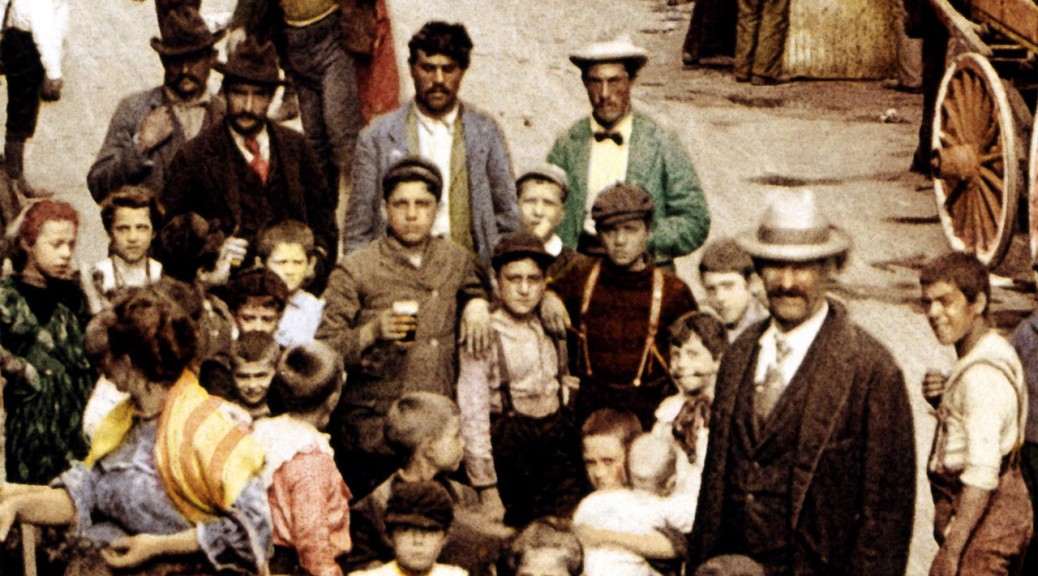

“The Italian-American Catholicism of the area was centered on street processions devoted to saints brought over from the old country: San Gandolfo for the Sicilians on Elizabeth Street, San Gennaro for the Neapolitans on Mulberry Street.”

“Spiritual Exercises” of St. Ignatius of Loyola (founder of the Jesuits)

“The exercises, devised in the 1520s, invite the “exercitant” to use his imagination to place himself in the company of Jesus, at the foot of the cross, among tormented souls in hell.”

Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins

“A.O. Scott, now a chief film critic for The New York Times, once wrote that Scorsese approaches filmmaking as “a priestly avocation, a set of spiritual exercises embedded in technical problems.””

“Like the novel, the picture interrogates the very idea of Christian martyrdom, by proposing that there are instances when martyrdom — the believer holding fast to Christ to the bitter end — is not holy or even right. It makes in the way of art the arguments made in defense of “Last Temptation”: that an act can’t be fully understood if the intentions behind it aren’t taken into account, and that a seeming act of profanation can be an act of devotion if done out of an underlying faith.”

“He will go to hell — but he will go to hell for their sake.”

bitacora. dic. 1

I wake up. Tiny claws scratching the wooden floor. A tongue lapping at the water. The dogs are ready to eat. Boil the water. Soften the food. I put Yolo in the pen. He demands to be set free. Chocolino come here. Treat time. Choco sit, down, beg, spiiiiiin, down, gidaria, eat. Repeat five times. Then his plate. Down. Gidaria. Eat. He wolfs it down.

Out the door. Elevator from the 5th floor to the first. The morning sun is bright. The city has already had a few hours to get started. I wait for 155.

The 155 is almost empty. I sit at the back on one of the single seats, and continue reading The Sound and The Fury. The 155 travels east. We cross the Suyeong at Millak. I look down at the water and try to come up something pretty. Nothing comes up. Just water moving toward more water. In India it would be spiritual. People get off at Centum. We turn north. I read. We turn at Jaesong and climb up toward Jangsan mountain. I hear the bus shift gears. People get off and on. A blue and white bus with red numbers driving up a city built on a mountain slope on a sunny morning in Korea. The market at Banyeo samdong, people with grocery bags, people reading their phones. We descend into Banyeo ildong. The view opens and a large slice of city appears framed by pine forests at each side, rows of tall monolithic white buildings beyond the basin of the Suyeong. The spine of the Geumjeongsan still green. The mountain disappears behind older and smaller houses. We enter Banyeon ildong. Narrow streets. A blue work truck parked at a tight corner. Honking. I read. We turn. The bus gathers speed. I hear the bus shift gears. We careen down the strip until the overpass. The whiny bell announces a passenger stop. An old lady with curly hair waddles to the backdoor holding the handrails as if enjoying an adventure at a moving jungle gym. I get off at the elementary school. The yellow leaves of the unheng tree strewn on the sidewalk. I think of my dad and how once as a kid I pretended to be a blind boy or an old man, using an imaginary cane to prod my way around the subsuelo hallway of the hotel. My dad frowned and asked me, ¿te haci de ciego o de viejo? I pondered the question. I looked at the corral my dad had been chatting with before he’d decided to test my morals. His friend looked back at me, grinned and waited for my response. I looked at my dad. De viejo, I said. Ah, bien, porque algun dia vai a ser viejo. I buy an ice americano at Amico for 2,500 won. The lady that made it hands it to me and bends the end of my straw so I won’t have to. I sip and exit the coffee shop.